The Underground Railroad in Illinois

After the Civil War, freedom seekers headed north toward freedom into Illinois. Even though Illinois was a free state, it was far from being a safe or welcoming place for them. The state’s Black Laws denied African Americans most fundamental freedoms (gathering in groups, voting, bearing arms, etc.), and the Fugitive Slave Act required residents to return freedom seekers to their owners. Many areas were patrolled, hoping to capture freedom seekers and return them to their owners for a reward.

This meant they had to travel through Illinois discreetly, usually under the cover of darkness. Freedom seekers would go from safe house to safe house—a path to freedom that came to be known as the Underground Railroad.

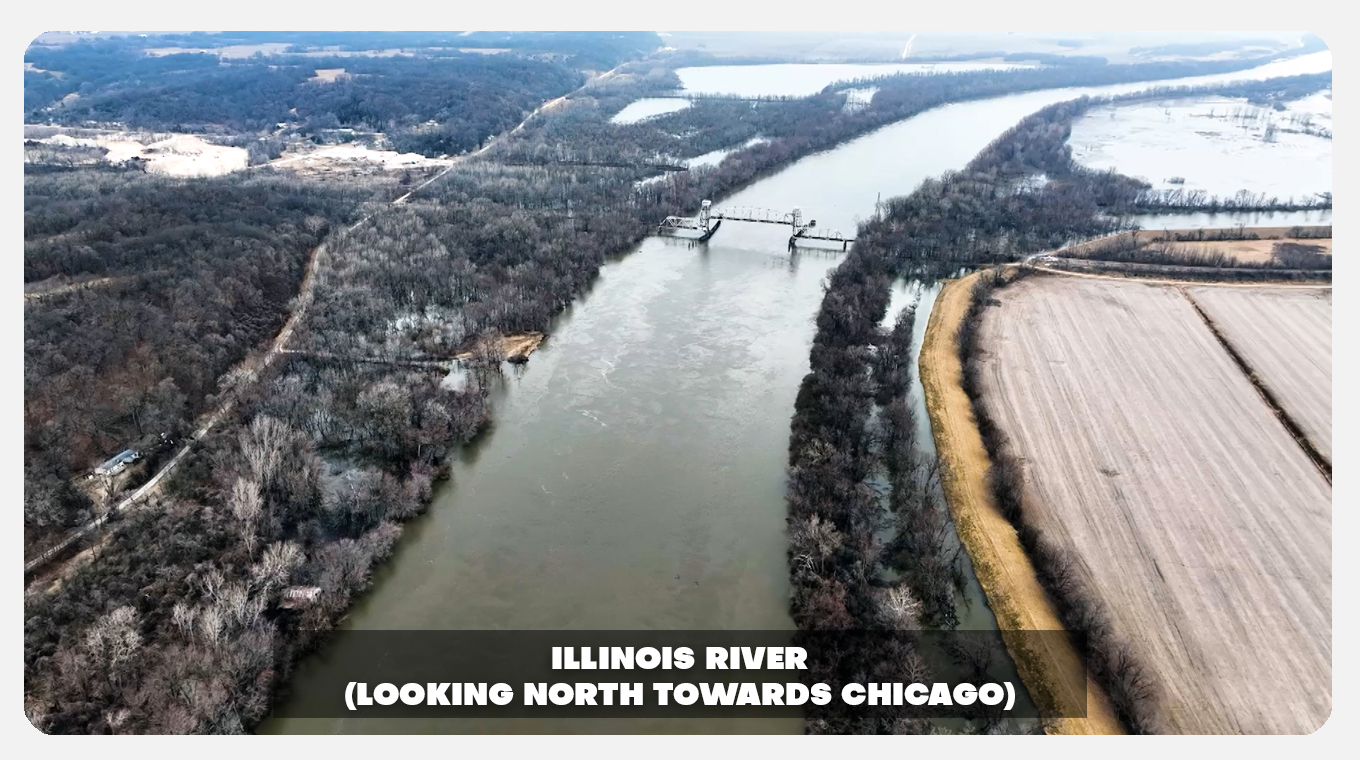

The Underground Railroad’s history in Illinois originates in the Southern part of the state, with freedom seekers using the natural routes of the two rivers that border the state as the main route. Some of the first known locations for Underground Railroad activity were found in these parts, and many towns in Southern Illinois still have traces of this rich history.

Illinois, with its proximity to slave states, played a significant role in facilitating escapes. The Ohio River touching Kentucky and the Mississippi bordering Missouri created a geographic advantage. Escaped slaves often sought refuge in the Illinois free black communities, strategically located in rural areas along the Illinois River. These remote locations, most of which would disappear during the Great Migration, provided a safe haven for those seeking freedom.

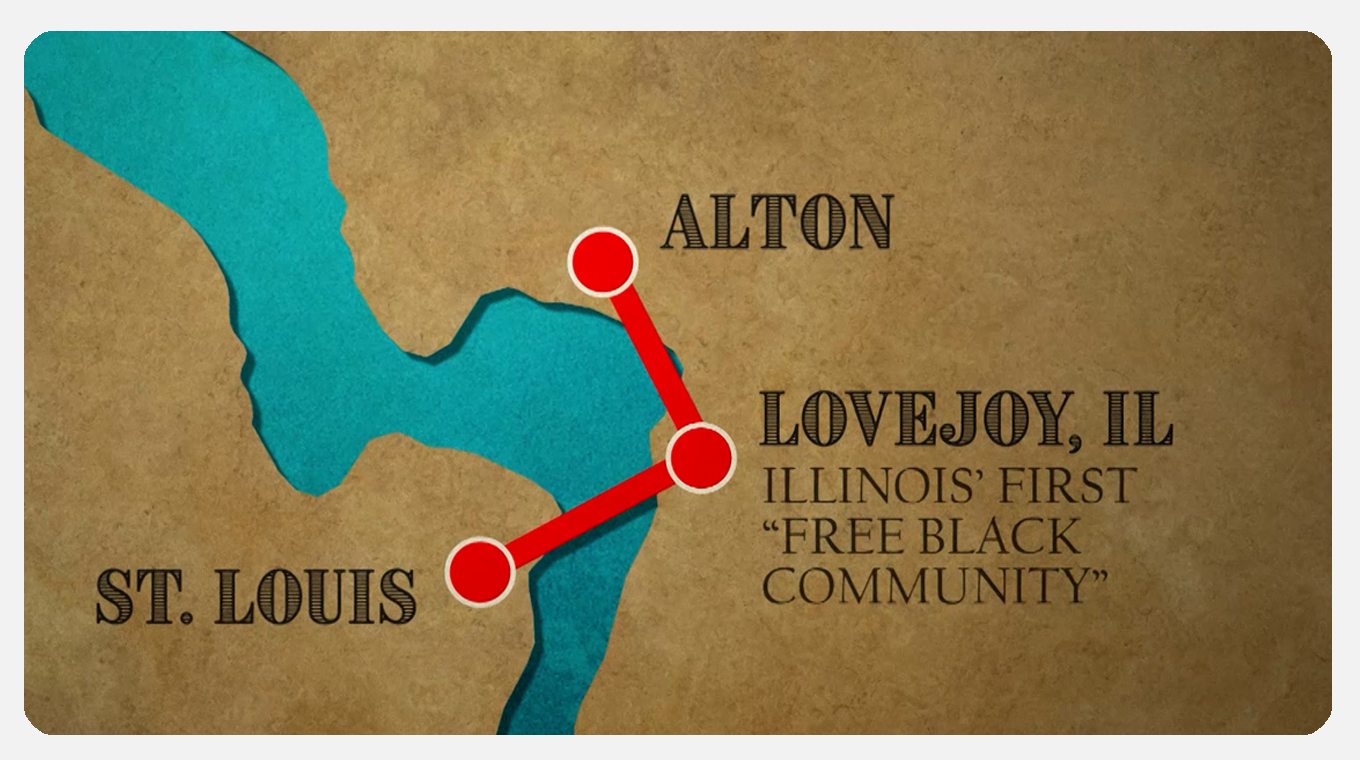

Lovejoy, Illinois (present day Brooklyn, IL)

According to oral history tradition, in 1829 "Mother" Priscilla Baltimore led a group of eleven families, composed of both fugitive and free African Americans, to flee slavery in St. Louis, Missouri. They crossed the Mississippi River to the free state of Illinois, where they established a freedom village in the “American Bottom”. Baltimore was said to have purchased her freedom as an adult from her master. She also bought the freedom of members of her family. Born in Kentucky, she tracked her white father to Missouri and bought her mother's freedom from him.

The Illinois River and its surrounding areas became strategic routes for escaped slaves heading towards the safety of Canada. Another river town just up the way from Lovejoy that would prove to be a pivotal stop on the Underground Railroad would be the town of Alton.

Alton, Illinois

Alton became an important town for abolitionists, as Illinois was a free state, separated from the slave state of Missouri only by the Mississippi River. Pro-slavery activists also lived there and slave catchers often raided the city. Escaped slaves would cross the river to seek shelter in Alton, and proceed to safer places through stations of the Underground Railroad. During the years before the American Civil War, several homes were equipped with tunnels and hiding places for stations on the Underground Railroad to aid slaves escaping to the North. On November 7, 1837, the abolitionist printer Reverend Elijah P. Lovejoy was murdered by a pro-slavery mob while he tried to protect his Alton-based press from being destroyed for the third time. He had moved from St. Louis because of opposition there. He had printed many abolitionist tracts and distributed them throughout the area. When one of the mob made a move to set the old warehouse on fire, Lovejoy, armed with only a pistol, went outside to try to stop him. The pro-slavery man shot him dead (with a shotgun, five rounds through the midsection). The mob stormed the warehouse and threw Lovejoy's printing press into the Mississippi. Lovejoy thus became the first martyr of the abolition movement.

Old Rock House - Alton

2705-2707 College Avenue

Located along the Mississippi River, it was a refuge for freedom seekers from Missouri and Southern slave states. Abolitionists and free blacks helped former enslaved people make it from one station to the next location on the Underground Railroad.

The Old Rock House was the home of Reverend Thaddeus Beman Hurlbut, who was the pastor of the Upper Alton Presbyterian Church (also known as the College Avenue Presbyterian Church) and a friend of Elijah Parish Lovejoy. It was built in 1834–1835 by Henry Caswell and John Higham. It was a double-dwelling building, with John Higham on the east side. In 1927, the house was owned by Dr. Isaac Moore.

The first meeting to organize the Illinois Anti-Slavery Society was held on October 26, 1837. From meeting notes, the meeting started at the church, but due to "disorderly elements", the meeting ended. It was rescheduled for the following day at the Rock House, where the society was organized. This happened just before the pro-slavery riots in Alton on October 28.

College Avenue Presbyterian Church and the Rock House are across College Avenue from each other. A historical marker for both buildings is located at College Avenue and Clawson Street

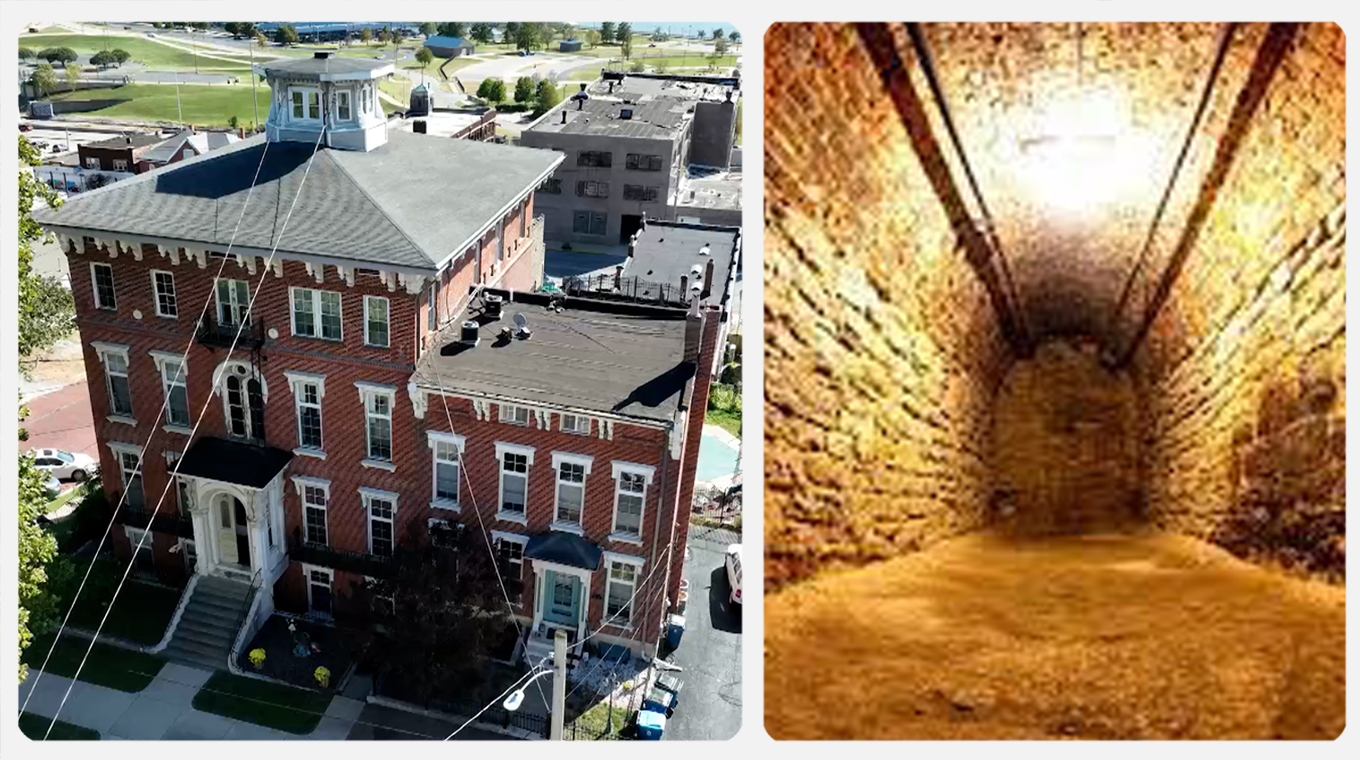

Enos Apartments - Alton

325 East Third Street

The basement of the four-story building, once a sanatorium and now the Enos Apartments, would have been among your escape routes. Historians say it was part of the Underground Railroad; a tunnel in the basement was a coal shed where escaped slaves hid.

The underground tunnels exist 15 feet below 3rd Street and resemble Roman catacombs. The basement of the apartment complex contains a sealed tunnel that reportedly held a passageway to hidden rooms where enslaved people rested during the day before traveling at night to the next stop on the Railroad.

Union Baptist Church - Alton

7th & George St.

From the Enos Apartment building, freedom seekers would make their way up George street to the Union Baptist Church. The stop had its origins in the summer of 1836, when 10 former slaves made their way to Alton. They first met at the home of Charles Edwards, and the group included such established city leaders as the Rev. Eben Rodgers of the First Baptist Church.

As more meetings followed, the group organized into the African Mission Freedman, which led to the founding of the African Baptist Church in 1837, with the Rev. John Livingston serving as its founding pastor.

The original church was a two-story frame building constructed in 1854 on the corner of Seventh and George streets. Now named Union Baptist Church, the church was located on the second floor, and Alton's first African-American school met on the lower level.

Falling on hard times, the church was forced to sell the property in 1876 and reverted to meeting in homes.

Wood Station, Foster Township - Near Alton

In 1819, the First Illinois General Assembly enacted a system that would limit the rights of free African Americans.

Despite these efforts, James Henry Johnson and Samuel Bates became some of the most prosperous landowners in the Foster Township of Madison County. Johnson and his wife, Eleanor, started the 80-acre Oak Leaf Farm in 1850 after moving to the Wood Station area of Foster Township. Not only did Johnson found and pastor Baptist churches in Alton, but he also represented Madison County at the State Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Illinois in 1856.

Bates and his wife, Martha Arbuckle, married and moved to Foster Township in Madison County in 1847. The brick house that Bates built for his family in 1865 still stands on Wood Station Rood at Seiler Road in Alton. Bates made the bricks himself.

Cheney Mansion - Jerseyville, IL

Dating back to 1827, the Cheney Mansion has plenty of history. The center part of the Mansion was the first structure built in Jerseyville and was called the ‘Little Red House,’ it was a stop for the Stage Line which ran through this part of the country. In the basement, there is a false cistern that slaves were hidden in, which served as a “station” for the Underground Railroad.

The station was a small underground room located beneath the mansion. A tunnel, discovered in the 1950s when State Street was being repaired, connected the room to a stable across the road. A trapdoor in the dining room allowed food and water to be lowered to those hiding below. The wall that once separated the basement from the underground room was removed by the Historical Society, so visitors can easily see the room.

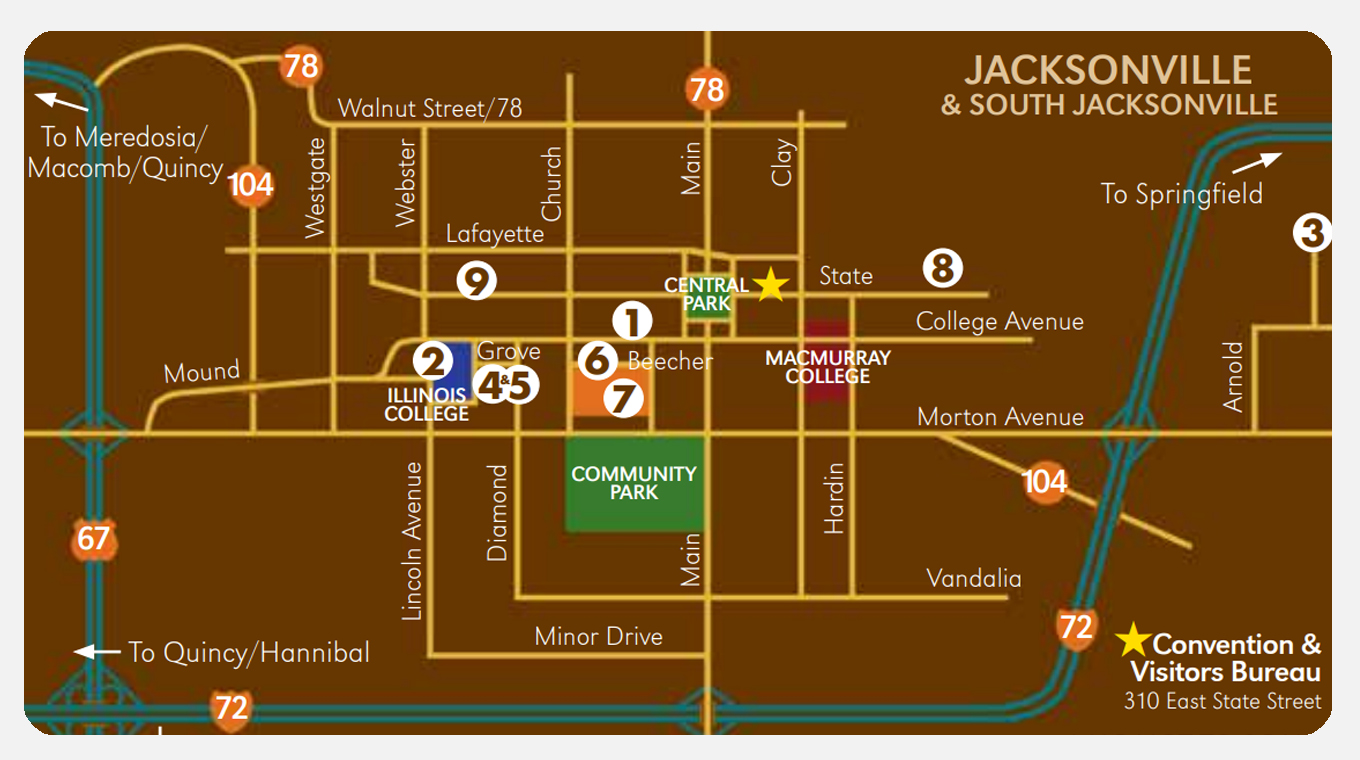

Jacksonville, IL

In the mid-1800s, Jacksonville, Illinois acted as a local hub for the Underground Railroad, sheltering hundreds who wished to escape the horrors of slavery. Several local historic homes served as havens on this journey to freedom, making Jacksonville one of the first such stations in the area.

Proud, educated abolitionists like Jonathan B. Turner and Edward Beecher, brother to Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, proved to be invaluable advocates for freedom. Edward Beecher was the first president of Illinois College, the first private college in Illinois. Because of the strong views of many of the students and faculty, Illinois College was considered an engine of abolitionism. Benjamin Henderson, a former slave, came to Jacksonville in 1841 and immediately began working with the Underground Railroad. These men and countless others kept the spirited torch of freedom burning bright.

In Jacksonville there are at least 9 documented sites which were important to this endeavor during the years before the Civil War. Most are private residences still available to be seen and their stories told.

1. THE FORMER CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH - 520 W. College Avenue

On December 15, 1833 thirty-two men and women founded the Jacksonville Congregational Church. They were all anti-slavery in belief and the church was soon called “the Abolition Church,” not always a compliment in the divided community of Jacksonville. When the UGRR became active in town, Deacon Elihu Wolcott was known as the “chief conductor.” Many members of this church bravely risked prison and fines by actively providing shelter, clothing, food and transportation. The Congregational Church is recognized by the National Park Service, National UGRR Network to Freedom program.

2. BEECHER HALL - Illinois College Campus

Illinois College was founded in 1829 by the “Yale Band,” a group of Yale theology graduates who left Connecticut to found churches and a college on the Western frontier. These young men were all opposed to slavery. The Rev. Edward Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, was named the first president. He was a good friend of the Rev. Elijah Lovejoy and together they founded the first Illinois Anti-Slavery Society in Alton. After Lovejoy’s tragic death the students held a massive protest near Beecher Hall. Students, professors and trustees of the College all were active in the UGRR. Beecher Hall and Illinois College are recognized by the National Park Service, National UGRR Network to Freedom program.

3. WOODLAWN FARM - 1463 Gierke Road

This farm was settled in 1824 by Michael Huffaker and his wife from Kentucky. Michael employed four free AfricanAmerican families for whom he provided cabins. In 1840 he built the home which still stands on the property. People were used to seeing blacks working on the farm and didn’t suspect that this was a safe house for “freedom seekers.”

4. DR. BAZALEEL GILLETT HOUSE - 1005 Grove Street

This home was purchased by Dr. Gillett in 1838.Construction began in 1833 and was finished by Dr. Gillett shortly after buying it. He was a physician who helped during the cholera epidemic of 1833. He also helped to found Trinity Episcopal Church and was one of the trustees of the Female Academy which merged with Illinois College in 1903. As an abolitionist he allowed “freedom seekers” to hide in an abandoned cabin on his 10 acres of land. One story tells of three women who were hiding in the shed and were rescued by Professor Jonathan Baldwin Turner of Illinois College.

5. ASA TALCOTT HOUSE - 859 Grove Street

This was the home of Asa and Marie Talcott, founding members of the Congregational Church. The home was built in 1833, with additions in 1844 and 1861. Asa Talcott was also a bricklayer and plasterer. Benjamin Henderson, a free black man and important conductor of the UGRR, stated that Asa Talcott was among those he could count on for help whenever he needed supplies for the fugitives. One story of a fleeing slave in February 1844 states that a slave was put in a haystack of Talcott’s barn, while authorities searched for the fugitive.

6. HENRY IRVING HOUSE - 711 West Beecher Avenue

Henry Irving moved to Jacksonville in 1842 and was an active member of the Congregational Church. His obituary from the Jacksonville Daily Journal states: “For a number of years after he came to this city he had the honor to belong to the brave band of Abolitionists who did so much to help fugitive slaves to freedom...His house was more than once a refuge to the freedom seekers.”

7. AFRICA IN JACKSONVILLE

In the 1800s most of Jacksonville’s African-American population lived in the area of town known as Africa. The area was bordered by W. Beecher Avenue (then known as College St.), S. West St., Anna St. and S. Church St. Here lived Ben Henderson, famous for his work in the UGRR and Rev. Andrew W. Jackson, pastor of Mt. Emory Baptist Church. In 1860 Africa had 156 residents. Many were former slaves who helped shelter “freedom seekers” on their way north.

8. GENERAL GRIERSON MANSION - 852 E. State Street

Garrison Berry owned a small brick home which originally stood on this property. One night he provided shelter for Emily Logan, who had escaped from her owner, Mrs. Porter Clay. The property was later purchased by the Grierson family and the original brick house was incorporated into the mansion. Benjamin H. Grierson, a general during the Civil War, later commanded the all black 10th U.S. Cavalry known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

9. PORTER CLAY HOUSE - 1019 W. State Street

The home was built in 1834 on six acres of land owned by Elizabeth Hardin Clay who had married Porter Clay, a brother of Henry Clay. She came from Kentucky with two of her slaves, Emily and Robert Logan. After living a while in Jacksonville, the young people learned that Illinois was a free state. Fearing that Mrs. Clay would send them back into slavery, they fled the home and hid with friends in Africa (site #7). Robert was recaptured and sent back south while Emily was hidden by friends in the Congregational Church until her freedom was granted by the Supreme Court (sites #1 & #8).