Trade Disputes Explode Under Trump Tariff War

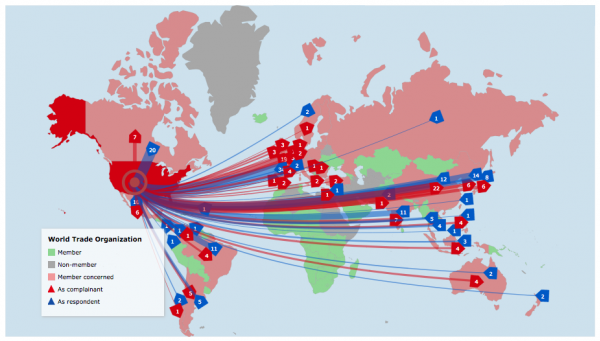

Since the creation of the World Trade Organization, the U.S. has been involved in 269 trade disputes. World Trade Organization

As President Donald Trump continues to wage a multi-front trade war with some of the U.S.’ biggest economic partners, farmers have borne some of the heaviest financial burden.

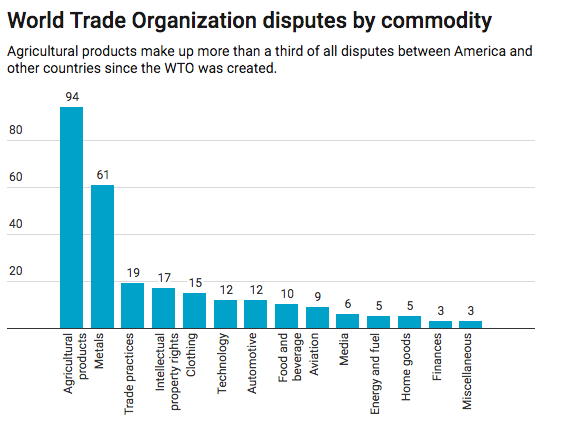

More than a third of trade disputes involving the U.S. relate to agriculture, according to an analysis of disputes submitted to the World Trade Organization since its creation in 1995.

Since Trump took office, the U.S.’ trade disagreements have focused on its biggest partners.

In the first half of 2018, Europe, Canada and China have each conducted more than $250 billion in trade with the U.S., and are among the top destinations for U.S. agricultural commodities, according to the USDA’s Economic Research Service.

Mexico, despite its fewer trade disputes, has also contributed nearly as much in trade.

In 2015, the U.S. exported more than $120 billion in agricultural goods across the globe.

“Looking at the landscape of things, it’s a fairly uncertain time for our industry. Those five markets make up about 60 percent of all U.S. ag exports,” said Veronica Nigh, economist for the American Farm Bureau Federation. “Between NAFTA renegotiations, pulling out of theTrans-Pacific Partnership, and the most recent disputes with China and the European Union, much of the American agricultural export market is under scrutiny.”

In the first half of 2018, the Trump administration has levied tariffs, or additional taxes on imported goods, on more than $400 billion worth of products from China, Canada, the European Union and other U.S. economic partners.

While Trump's tariffs have focused on foreign steel, aluminum and intellectual property rights, retaliation from other countries has hit agriculture hard.

Scott Vanderwal, farmer and president of the South Dakota Farm Bureau explained how the focus on steel and aluminum would hurt American Farmers at a hearing before the Congressional House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Trade in July.

“According to the USDA Foreign Ag Service, 95 percent of the exports from our state go to the top steel exports. Eighty-four percent of our exports go to the top aluminum exporters,” said Vanderwal. “Those countries know just how to punch us back in a dispute situation, andthat’s agricultural products.”

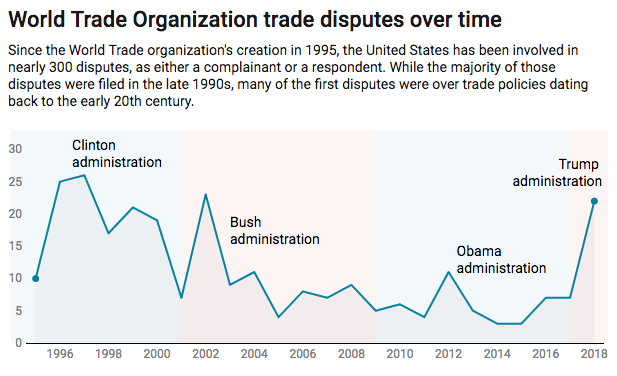

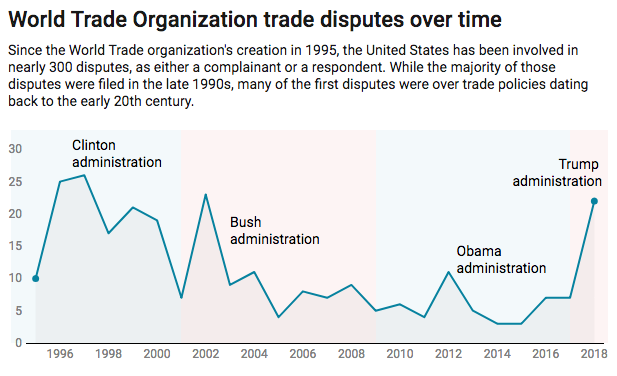

U.S. trade disputes over time

The World Trade Organization was created in 1995 to operate a global system of trade rules, help negotiate trade agreements and oversee trade disputes.

Chart: Christopher Walljasper/Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting Source: WTO

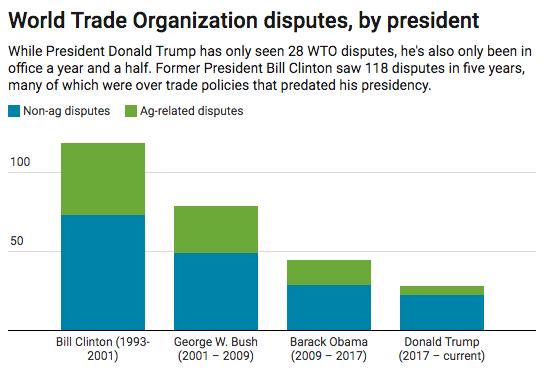

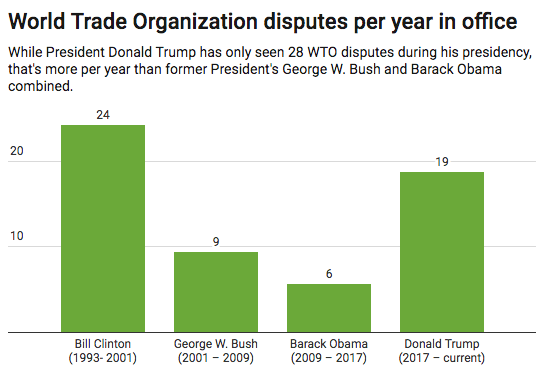

Since Trump took office in January 2017, 28 trade disputes have been filed involving the United States.

Chart: Christopher Walljasper/Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting Source: WTO

While that pales in comparison to his predecessors, it’s only been a year and a half since Trump took office. Former President George W. Bush and former President Barack Obama averaged nine and six disputes a year, respectively.

Chart: Christopher Walljasper/Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting Source: WTO

Chart: Christopher Walljasper/Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting Source: WTO

In all, 269 disputes have been filed involving the U.S. in the last 23 years.

U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer said in a statement, U.S. tariffs on steel and intellectual property are justified to “defend our economy from unfair trade practices and work to advance free, fair and reciprocal trade relationships.”

USDA Secretary Sonny Perdue said that using tariffs against U.S. agriculture to retaliate is the wrong way to solve trade disputes.

“At every step along the way during these recent trade disruptions, it is important to highlight that the correct action from other nations would be to stop their bad behavior – not to retaliate with unjustified tariffs,” said Perdue.

2018 trade based on U.S. Census Bureau data for the top 15 U.S. trading partners. European communities does not contain trade with all European nations.

Impact on Agriculture

The Trump administration is using a depression-era program to provide $12 billion in aid to farmers and ranchers feeling the pinch from Trump's trade strategies and subsequent retaliation, but some call the package a temporary fix to a problem that may persist beyond harvest.

In his July announcement of the aid program, Perdue said the president’s negotiation tactics were working.

“It is clear to everyone that President Trump has gotten China’s attention like never before,” said Perdue. “Unfortunately, America’s hardworking agricultural producers have been treated unfairly by illegal trading practices by China and other nations and have taken a disproportionate hit when it comes to unjustified retaliatory tariffs.”

Not all agriculture exports are at risk as the administration tries to crack down on what it sees as unbalanced trade. But as Michelle Erickson-Jones, a Montana wheat farmer explained to the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Trade, even the steel and aluminum tariffs the U.S. has levied are hurting farmers.

Erickson-Jones described pricing a new grain bin for storing grain on the farm. While the price of the bin had increased 12 percent compared to bin they built a year before, over the course of a few weeks, the cost jumped another 8 percent, due to the increased cost of steel.

“As a result of this dramatic cost increase and volatility in the market, we abandoned our grain storage expansion project,” she said. “The implications of that not only harm my operation, it also hurt my community. A small local construction company lost a project, a U.S. grain bin company missed a sale and a domestic steel company had one less shipment to send out of their factory.”

More immediate is the risk for farms as they prepare for discussions with lenders later this year.

“We know the bankers are extremely worried,” said Vanderwal.

The dip in price per bushel directly correlates with a farmers’ ability to repay an operating loan.

“The last thing a lender wants to do is sit across the desk from one of his customers and say ‘I'm sorry but we can't renew your loan for this next year. You're out of business, he said.

Nigh said the $12 billion aid package could assuage lenders’ concerns, but notes it is only temporary and doesn’t make up for lost trade.

“It’s a lot of money, but there’s a lot of farmers and there’s a lot of commodities that have experienced a significant amount of hardship as a result of these trade actions.” said Nigh. “Overall though, it will not make farmers whole.”

Lost markets

And a prolonged trade war could damage hard-fought markets for U.S. grain and meat.

“We cannot afford to lose our place at the table as a leader in the global marketplace,” Said Kevin Paap, president of the Minnesota Farm Bureau. “If we’re not at the table we will be on the menu.”

Nigh said convincing China to come back to American grain will be difficult once it’s committed to buying from South America, since animal feed is especially formulated.

“If I’m the customer and I start using Brazilian products instead of U.S. products, and I’ve got the formula down, I’m happy with the product I’m getting. What incentive is there for me to go back to the former supplier?”

Even if new markets open up, Nigh said, American farmers will be selling their grain at a discount.

Soybean exports in metric tons.

Farmers for free trade and Trump

For Russell Boening, a farmer, rancher and the president of Texas Farm Bureau, Trump’s complaints against Chinese trade practices are justified, even as his own farm suffers. He points out that in one year, China’s subsidies for corn, rice and wheat were more than $100 billion above its WTO commitments.

“We just finished a hard-fought farm bill debate where some people question the need for support provided to our farmers,” Boening said. “But China's illegal subsidies for those three crops in one year exceeded what we will spend on the entire farm safety net for every crop on every acre for the entire life of the farm bill.”

At the House subcommittee meeting, three of the five farmers reiterated support for Trump and his trade efforts. Nigh said farmers benefit from free trade.

“Every trade agreement that’s been negotiated by the U.S. has been, on net, good for U.S. agriculture,” said Nigh.

“We’d like to get back in the game of negotiating new agreements,” she said, “so we can get back to focusing on growing our markets rather than defending them.”