Supreme Tort: The Campaign To Fire Justice Lloyd Karmeier

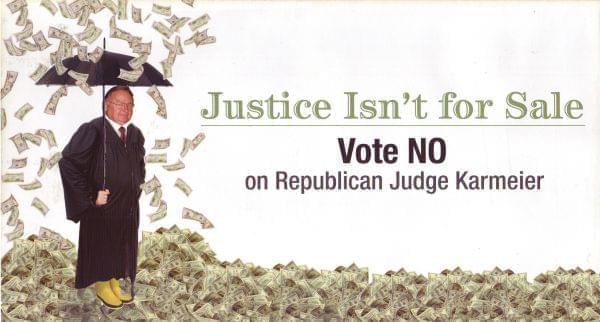

Some anti-Karmeier ads focused on plaintiffs' lawyers claims that State Farm and Philip Morris bankrolled his original 2004 campaign.

No justice of the Illinois Supreme Court has lost a retention election since the up-or-down system was put in place 50 years ago. Last fall, Justice Lloyd Karmeier came close. He squeezed into another decade on the bench with just 2,921 votes to spare — less than eight-tenths of a percentage point above the required 60 percent threshold. His brush with late retirement — Karmeier turned 75 in January — was brought about by a nasty, last-minute advertising blitz for which the judge was ill-prepared.

At the heart of the matter is a significant question of legal ethics. But just what that question is depends on whom you ask. The small group of lawyers who tried to defeat Karmeier say his entire career on the high court is tainted. They allege his original 2004 campaign for the Supreme Court received financial support from a pair of big corporations, and that he then ruled in favor of those companies once he was on the bench. In this version of the story, the biggest problem is so-called dark money infecting the judicial election process — campaign cash laundered through layers of non-profit and party organizations, masking its origin.

This version of events, however, has yet to be proven in court. And regardless, Karmeier rejects the allegations. He maintains he has never looked at the list of financial supporters from the 2004 campaign. From his perspective, the ethical issue is that most of the money opposing his retention came from lawyers who have cases that directly implicate Karmeier, either as a judge or a potential witness. The entire effort, which raised more than $2 million in a matter of weeks, was financed by a combination of just seven individuals and law firms.

“Until lawyers have some ethics about what they’re doing, it’s going to be difficult to stop this,” Karmeier says. His opponents aren’t giving any ground, either. “The guy does not deserve to be on the Illinois Supreme Court,” says Joseph Power, whose firm helped fund the anti-retention effort.

The cloud that’s been raining on Karmeier’s Supreme Court career comprises two cases.Avery v. State Farm is a $1.05 billion class action lawsuit in which a jury decided the insurance company used inferior, aftermarket parts to repair damaged vehicles. It was a record award in Illinois, but it was soon overtaken by a $10.1 billion victory in the class action Price v. Philip Morris. In that case, the plaintiffs convinced a judge that the tobacco company defrauded customers by marketing “light” cigarettes as less dangerous than regular cigarettes.

Both cases were appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court before Karmeier had even decided to run. The 2004 campaign pitted Karmeier, a Republican trial judge in Washington County, against Democratic Appellate Justice Gordon Maag, of the Fifth District. It became an epic fight between Republicans and big business on one side, and Democrats and trial lawyers on the other. It was also the most expensive judicial election in American history, with both sides combining to raise $9.3 million.

Although Avery v. State Farm had been argued in May 2003, it was still pending in December 2004, when Karmeier was sworn in. According to a timeline provided by Karmeier, he initially wasn’t going to participate in the case. But when his colleagues were still deadlocked in January 2005, Karmeier stepped in, voting to join the majority opinion overturning the billion-dollar victory. Eight days later, lawyers for the plaintiffs filed a motion asking that Karmeier not participate in Avery. The full court initially denied the motion, but eventually ruled it was for Karmeier to decide alone. He stayed in. On August 18, 2005, the justices issued a 4-2 decision in favor of State Farm. The next year, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal. With that, the case was dead. Or so it seemed.

In 2011, the plaintiffs’ lawyers asked the Illinois Supreme Court to revive Avery v. State Farm. They alleged State Farm played a significant role — greater than previously known — in Karmeier’s 2004 election, tainting the court’s opinion. The court denied the motion, this time with Karmeier sitting out. But it didn’t end there. In 2012, the attorneys literally made a federal case out of the matter: Hale v. State Farm, a civil racketeering suit filed in the Southern District of Illinois. Now the plaintiffs alleged State Farm recruited Karmeier, ran his campaign from the shadows and secretly provided most of the money for it, all so he could rule on Avery.

State Farm denies these allegations. And while Karmeier is not among those being sued, the lawyers for the plaintiffs — including Robert Clifford — wanted to depose him. Clifford is one of the biggest names among Chicago plaintiffs’ lawyers, and his firm, Clifford Law Offices, gave $250,000 to the campaign to unseat Karmeier. “I believe that the voters have a right to know who their judges are, the voting record of the judges, and what their sources of campaign funding have been,” Clifford says.

Clifford’s effort to use the discovery process to investigate the case has been repeatedly blocked by Magistrate Judge Stephen Williams. In January, he declined to let Clifford breach State Farm’s attorney-client privilege: “Plaintiffs allege that State Farm contributed in excess of $4 million to Karmeier’s campaign, but at this time plaintiffs are not able to connect the dots on the money trail from State Farm to the Karmeier campaign.” Williams also says Karmeier does not have to sit for a deposition: “Setting aside whether or not at some point plaintiffs may offer some evidence of Justice Karmeier’s complicity in the fraud alleged in the Amended Complaint, thus far they have offered nothing of the sort.” Karmeier will, however, have to answer a limited set of written questions about the 2004 campaign.

From Karmeier’s perspective, all this is beside the point. He says he never looked at fundraising records. “When I was running in 2004, the given way for judges to do it was to simply avoid and not know, and then you couldn’t be considered having any bias or problems,” Karmeier says. A decade ago, when he got the first recusal motion from the Avery plaintiffs, Karmeier asked his clerk to look at his campaign disclosures to see whether State Farm was there. It was not. “As far as I was concerned, that was all hyperbole, and all a creation, and still is,” he says.

Many of the allegations against Karmeier regarding State Farm are similar to those made in Price v. Philip Morris. As in Avery, the oral arguments had been completed by the time Karmeier joined the court, and Karmeier’s participation was essential to reaching the four-justice plurality required to issue an opinion. On December 15, 2005, the high court issued another 4-2 decision, this one overturning the $10.1 billion judgment against Philip Morris. The majority reasoned that because the Federal Trade Commission had authorized the use of “light” and “low tar” to describe cigarettes, Philip Morris could not be found to have committed fraud. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review Price, but in a different case in 2008, the FTC clarified that it never in fact authorized “light” or “low tar.” The plaintiffs thought that undercut the Illinois Supreme Court’s decision, so it sought to reinstate their case.

Though they had not done so a decade ago, last year the plaintiffs asked Karmeier to recuse himself. The allegations have a familiar ring: mainly that Philip Morris provided the majority of funding for Karmeier’s campaign. Never mind the mathematical peculiarity of State Farm providing “as much as $4 million” and Philip Morris providing “almost $3.4 million” to a candidate who received a total of $4.66 million. This time, the lawyers had something else on their side: the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2009 decision in Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co. A Massey executive openly spent $3 million to help elect a judge to the West Virginia Supreme Court while an appeal of a $50 million judgment against his company was pending. The court found that created “a serious risk of actual bias.” The Price plaintiffs argued that’s exactly what happened with Philip Morris and Karmeier.

The Illinois Supreme Court almost exclusively responds to such motions without comment, but Karmeier opted to file a 16-page order. Unlike in Caperton, Karmeier’s campaign finance records indicate no contributions from Philip Morris. “In reality, the notion that [Philip Morris] was responsible for financing my run for office ten years ago is just that, a notion,” Karmeier wrote. “It is based entirely on conjecture, innuendo and speculation which, once started, took on a life of its own for awhile in the press.” Karmeier, once again, would remain on the case.

“This matter comes before the court on the eve of my retention election,” Karmeier wrote. “My decision today may have an effect on my candidacy. That, however, is an occupational hazard in our system for electing judges.” The order was published September 24, 2014.

On the afternoon of October 17, Karmeier heard from his old friend Dave Luechtefeld, a Republican state senator from Okawville. “This is the telephone call you didn’t want to get,” Karmeier recalls him saying. During the next two-and-a-half weeks, a political action committee called Campaign for 2016 spent more than $2 million attacking Karmeier. Some ads claimed he was in bed with State Farm and Philip Morris. Others bashed his decision to side with the majority that kept free health care for many state retirees, whom the ad dubbed “supervillians.” A mailer targeted at Republicans even called him a “liberal judge.”

The Campaign for 2016 was a sneak attack. By the time he got the call about the negative TV ads, Karmeier had only raised about $141,000, and spent a fraction of that on radio and newspaper ads, a palm card and two campaign employees. “We did not expect this,” Karmeier says. “I was surprised by the tone, the intensity and by the people who were behind it.”

Among the four people and three law firms that bankrolled Campaign for 2016, all but one has direct ties to either the State Farm or Philip Morris cases. Joseph Power, whose Power, Rogers & Smith firm gave $260,000, is counsel of record in the Philip Morris revival, as is George Zelcs, who personally gave $600,000. Zelcs and Christine Moody — another $600,000 contributor — are both with St. Louis-based Korein Tillery, the lead plaintiffs’ firm in the Philip Morris case. Stephen Tillery declined to comment because Price is still pending before the Illinois Supreme Court.

Power, however, has no such reservations: “Justice Karmeier is opposed to everything I stand for.” He singled out a Karmeier dissent in which the justice said he would have upheld limits on pain-and-suffering damages in medical malpractice cases. But isn’t there something ethically dubious about a group of lawyers trying to take out a judge before whom they have a pending case? “Everything that was done by us was done above-board,” Power says. Although some of the lawyers in the anti-Karmeier effort have more than a billion dollars in fees on the line, they insist their campaign was about educating the public. They say they want to get “dark money” out of judicial elections. “I would suggest that if we did it the way the Karmeier people did it, we would have had a lot more attorneys supporting the effort,” Power says. “But the fact that we had to reveal the names, in our opinion, caused a lot of lawyers to be hesitant.”

While the lawyers who claim Karmeier’s campaign was funded by State Farm and/or Philip Morris have yet to prove that in court, it is true that Karmeier has been the beneficiary of large sums of money whose origins are difficult to trace. Within a week after the campaign against Karmeier’s retention was launched, an independent expenditure group called the “Republican State Leadership Committee-IE Committee” got a $950,000 contribution to try to save Karmeier’s position. Illinois campaign disclosures reveal the money came from … the “Republican State Leadership Committee Inc.” That circular disclosure is the kind of opacity Power and his collaborators are criticizing.

An RSLC disclosure, filed with the Internal Revenue Service after the 2014 elections, does show that in 2014 it received more than $1 million from Altria Client Services. Altria, of course, is the conglomerate that’s home to Philip Morris. But RSLC funded campaigns across the country, and the last of Altria’s contributions came October 8, more than a week before the campaign to unseat Karmeier revealed itself — that is, before Altria, the Republican Party, or Karmeier himself could have known he would need help. Karmeier, again, would say this is beside the point. He says he’s made it his practice to not look at campaign contributors — at least not until after the election this year.

After Kyle Deatherage, an Illinois State Police trooper, was struck and killed by a Dot Foods truck on Interstate 55, his widow sued the company. Dot wanted the case transferred out of Madison County, but a trial judge said no. Then the Fifth District Appellate Court declined to hear the appeal. The Supreme Court’s order — unanimous and routine, according to Karmeier — tossed the case back to the Fifth District with orders to hear Dot’s argument. This time, the appellate court granted Dot’s request.

Nearly a year after the Supreme Court’s order, Dot and one of its executives contributed a total of $11,000 to Karmeier’s retention campaign. Belleville attorney Tom Keefe represents Sarah Deatherage. He says she was outraged when she heard about the donation. The two held a press conference in October at which they accused Karmeier of … it’s not exactly clear what. “I was very careful, and Sara was very careful, not to accuse Judge Karmeier of taking any money. I don’t have any proof of that.” Keefe says he was acceding to Deatherage’s request to hold the press conference. “It wasn’t my smartest career move, but I stand by it.” He says he’d been friends with Karmeier for 25 years, but says it was wrong for Karmeier to take money from a litigant on whose case he’d already ruled. Karmeier rightly points out that at the time Dot made the donations, the company had no case pending before the Supreme Court. And he maintains he was not aware of his campaign contributors — at least not until Keefe called him out. But Keefe is skeptical: “I don’t find it credible for one reason: the email.”

"How, one might wonder, would someone obtain the personal emails of a Supreme Court candidate?"

The email. It’s been a fixture of anti-Karmeier efforts for more than a decade. The email first surfaced as part of an anonymous drop to reporters during the 2004 campaign. It’s also part of the evidence filed with the motion asking Karmeier to step down from the Philip Morris revival. The key message, purportedly from Ed Murnane of the Civil Justice League, was sent to Karmeier during the 2004 campaign: “The spending report includes contributions from (close your eyes, Judge…) Illinois State Medical Society and Justpac -- both $5000.” (How, one might wonder, would someone obtain the personal emails of a Supreme Court candidate? Korein Tillery, the firm suing Philip Morris and whose attorneys spent $1.2 million trying to boot Karmeier, hired a private investigator who says he recovered the messages during a regular dive into Luechtefeld’s trash.)

Assuming for the sake of argument that Karmeier saw this email, it would belie his suggestion of total ignorance about his 2004 campaign financiers. “I want to be so clear about this,” Keefe says. “I am not saying that a Supreme Court justice isn’t telling the truth. But if you’re asking me whether or not Justice Karmeier says he looked at anything? … One would have the right to scratch their head based on the previous email.”

Karmeier is angry about the campaign that almost ousted him. He says he dislikes the course of both his campaigns, but the 2014 retention was worse than the record-breaking 2004 mud-slinging fest between he and Maag: “Then it was political. It was Republican against Democrat. It was a philosophy of perhaps being more liberal in certain areas and I was more moderate or conservative. And that’s OK,” he says. “But when you get into a retention election, if you’ve done your job — unless there’s been problems, and there’s never been any criticism that I haven’t shown up for work or I haven’t done my share or that I haven’t tried to be fair — suddenly a group of … lawyers says, no, we’ve got to change this. And spend $2 million. It seems to me a little different.”

Some of the lawyers who tried to unseat Karmeier say conservative activists cast the first stone when they tried and failed to sink then-Chief Justice Thomas Kilbride’s retention in 2010. “Oh yeah, and that was sponsored by a group that supported me 10 years ago, unfortunately,” Karmeier says, referring to the Civil Justice League. “[That’s] very disappointing.”

Karmeier acknowledges the problems inherent in a system in which judges must fundraise and stand before voters looking very much like legislative and executive branch politicians. “The fact that somebody gives you money, we consider that a quid pro quo for politicians. Not just necessarily that they’re going to be favorable, but ‘maybe we can get a special favor.’ Why wouldn’t you think the same thing about judges?”

A version of this story appears in the February 2015 edition of Illinois Issues magazine.