Meet The Midwestern Man Who’s Saving The Forgotten Grapes That Saved Europe’s Wines

Jerry Eisterhold runs Vox Vineyards in Weston, Missouri. Here's working to save long-lost American wine grape varietals. Laura Ziegler/KCUR 89.3

With the help of a rented plane, Jerry Eisterhold found the perfect place to start a vineyard with grapes native to the Midwest, grapes that no one had cultivated for more than 150 years.

A soil scientist by training, he liked the dirt on the Missouri River bluffs north of Kansas City, Missouri.

“The Missouri River was the edge of the Ice Age sheet,” he said earlier this year while standing on the balcony at Vox Vineyards, six rolling acres of grapevines just outside Weston. “The soil is thinner with smaller particles. (It’s) not high in organic matter or vegetative growth, which is what we want when we’re interested in fruit.”

These grapes are hearty enough to thrive in the Midwest’s typically cold winters and hot summers and are highly resistant to pests. The grapes also saved the European wine industry, allowing people today to enjoy chardonnays and cabernets.

Wine expert Doug Frost tastes one of Jerry Eisterhold's creations. He says the best wines impart the flavor of their soil.

The best wines say something about the soil, the climate and even the culture where the grapes are grown, according to Doug Frost, a wine expert with the rare combination of both a Master of Wine and Master Sommelier.

“(When) you taste a wine, you can say to yourself, I can’t taste this any place except this one place north of Kansas City that has this grape growing there and it tastes just like this,” he said. “That uniqueness is what you hope for.”

The history

Eisterhold, who grew up around Hermann, Missouri, which is a major player in the Missouri wine business, wanted to make unique wines. And it all started when he pulled a random, rare, tattered book from his shelf.

The Foundations of American Grape Culture is by 19th-century horticulturist Thomas Volney Munson. The Illinois-born botanist made it his life’s work to collect and classify grapes native to America, particularly in a line stretching from Nebraska to Missouri, Arkansas down to north Texas, where he eventually settled.

Munson’s work was so well-known that when European vines began to die because of a deadly phylloxera aphid (due to imports from America), growers turned to Munson because they knew he’d been hybridizing American varieties. They asked him to send some phylloxera-resistant rootstock, which was grafted on to the infected European varieties.

Since then, Munson has been recognized for saving the European wine industry, even being awarded the distinguished Chevalier du Merite Agricole by the French Legion of Honor.

But after Munson’s death in 1913, his vines and some 300 varieties of grapes fell into obscurity.

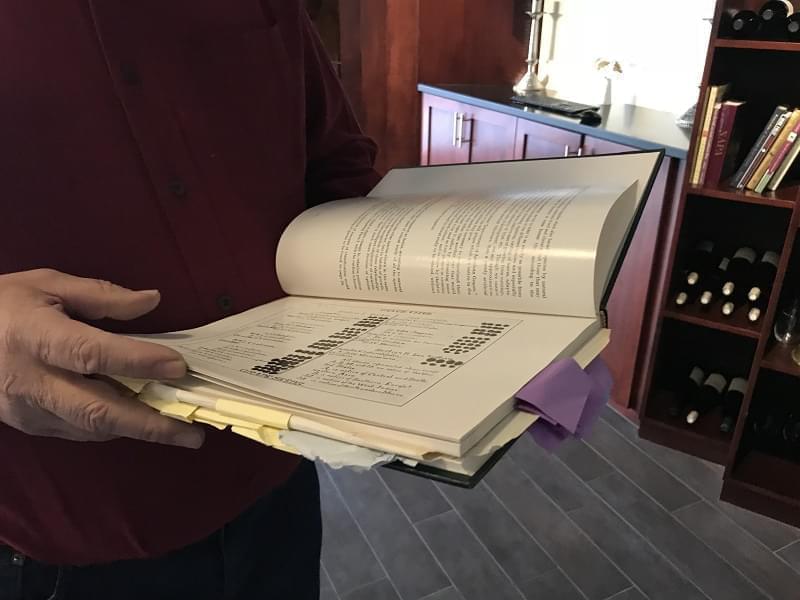

This book on Thomas Volney Munson inspired Jerry Eisterhold's work to save now-forgotten Midwestern grapes.

Preserving a legacy

And that’s where Eisterhold comes in. He’s located the vines on the grounds of what is now a community college in Texas and found someone to send him cuttings.

Flipping through the pages of Munson’s book, which is tagged by yellow sticky notes, Eisterhold pointed to hand-drawn illustrations of the different varieties.

“(I say,) you know I’d like to try this one and this one and this one,” he said. “(I) write and ask for cuttings. I get half of them, root them, and half of them root. It’s taken about 15 years to get the vines I have out there.”

Clark Smith, whom Eisterhold has as a consultant, said Munson’s work is valuable to the history of horticulture. Plus, he said, some of the grapes are really good.

“I mean imagine if nobody knew about Mozart, and then all of a sudden somebody dug up his work and people said, ’this guy wrote some good stuff,’” Smith said. “It’s like that.”

The balcony outside of the tasting room at Vox Vineyards overlooks what were still-naked vines in early 2018. Below, a worker shoveled soil into beds where his team will start growing cuttings for next year’s crop.

Every bottle of Terra Vox wine includes a picture of Thomas Volney Munson, the philosophical father of Vox Vineyards.

Eisterhold sells his wines under the label Terra Vox, or “voice of the land.” He likes to say Munson’s work was a “conversation” between the grapes and the land — and he wants to preserve it.

“He was a little bit of a philosopher,” Eisterhold said. “He had the idea that agriculture and the plants and animals we deal with are not fixed things, that they need to evolve. So all this is kind of trying to pick up on the wave he started.”

Laura Ziegler is a community engagement reporter and producer at KCUR 89.3. Follow her on Twitter: @laurazig or reach her via email at lauraz@kcur.org.