Indiana Hematologist Hits The Road To Prevent Children From Having Strokes

Dr. Emily Meier runs a quarterly hematology clinic in Lake County, Indiana to fill the gaps in pediatric care. Emily Forman/Side Effects Public Media

Doctor Emily Meier usually practices hematology at the Indiana Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center in Indianapolis. But four times a year Meier and her team drive two hours north to Lake County, Indiana and host a clinic for children diagnosed with sickle cell disease.

During her visit in May, Meier met with a couple and their newborn son. They huddled around a brown felted doll with velcro flaps on its legs to show the difference between healthy blood cells and sickled cells.

“Usually the red blood cell looks like a donut. It's round shape and it moves very smoothly through all of the blood vessels,” Meier explained to the new parents.

Children with sickle cell disease have sensitive bodies. Anything from dehydration, to fever, to a change in altitude can affect their red blood cells.

In a pain crisis, sickle cells, that look like red crescent moons, catch on each other as they move through the bloodstream and create traffic jams in blood vessels. A block can lead to stroke.

This is what worries Meier the most. “It keeps me up at night worried about their brains,” she said.

Meier teaches new parents how to locate their baby's spleen in an education session about what to expect with sickle cell disease.

Meier said children with sickle cell disease need to get screened for stroke but doctors in the region miss this step. This was part of the reason why Meier and her team started going to Lake County to provide medical care.

“People in Lake County are not getting the same level of healthcare that the rest of the state is getting and that's because there's no board certified hemotologist up here to give that level of care,” she said.

The test to determine if a child diagnosed with sickle cell disease is at risk for stroke is called a transcranial doppler or TCD screen. It’s basically an ultrasound for your head. If a child is at risk for stroke they need chronic blood transfusions and a medication called hydroxyurea to prevent it.

Meier said Lake County providers are the worst at offering TCD screens to families. “We know that only about 20 to 30 percent of the children were getting the screenings in Lake County compared to the rest of the state where 70 to 80 percent of the kids were getting that screening,” she said.

The clinic recently trained an ultrasound technician in Lake County to do TCDs screens. So now they have somewhere to refer families and Dr. Meier can have a little more peace of mind knowing more kids will get tested.

Meier and her team discovered the disproportionately low screening numbers in Lake County when they began tracking all Indiana babies born with sickle cell disease. “I think we had 56 babies born last year with sickle cell and I think seven or eight of them were in Lake County,” Meier estimated.

Since 2009, everytime a newborn tests positive for the disease the Indiana State Department of Health faxes the results to Meier’s office. Then social workers on Meier’s team follow up with families. They make home visits, document children's medications and vaccines, as well as link them to care.

In addition to vaccines and medication checks, the clinic's social workers connect families with activities like summer camp for children with sickle cell disease.

The Department of Health and Human Services maintains a list of recommended illnesses that states should screen newborns for. HHS added sickle cell anemia to the list in 2006. In 2009, Indiana passed legislation to add the disease to its newborn screening panel. So, if a child was diagnosed with sickle cell prior to 2009, they won’t be on Meier’s radar.

Grant funding through the Indiana State Department of Health pays for Meier’s mobile clinic. It also covers three months worth of penicillin for any baby born with sickle cell disease in Indiana. Meier’s team now plans to analyze statewide medical records to estimate a how many people in Indiana have sickle cell, something that isn’t known.

Meier described the landscape of sickle cell care in Lake County as disjointed especially in hospital emergency rooms. She has plans to give presentations at a few in the region to spread more information about caring for sickle cell patients.

Inconsistent care in the ER in Lake County, is something Alexandria Reed has experienced first hand with her seven year old daughter, Mylah Carman.

Reed said Mylah’s pediatrician has managed her sickle cell since birth but isn’t always on call when she has a crisis. When Mylah has trouble breathing or unbearable pain she needs to go to the emergency room. Reed said the last time she went to the ER the staff didn’t believe Mylah had sickle cell.

“I was telling the nurses she's having a hard time breathing. And they kept on saying ‘Oh she's ok. She's ok.’ Next thing I know she's not responding and people running in,” she said.

The hospital had to send Mylah two hours south to Indianapolis for oxygen and a blood transfusion. Respiratory issues in sickle cell patients are a big concern because it can lead to death.

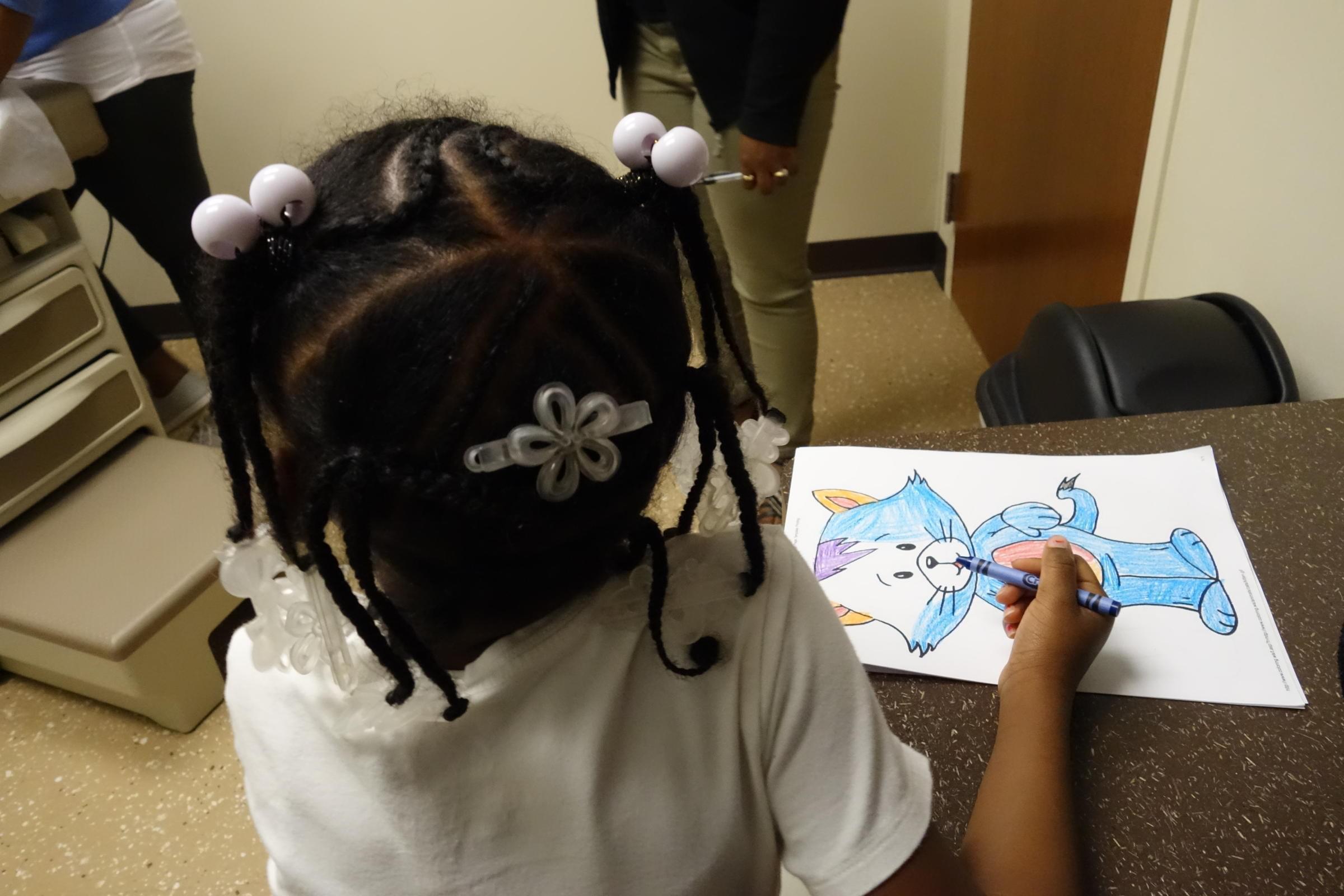

Alexandria Reed and her seven year old daughter Mylah Carman visit the clinic for the first time.

Last month, was Mylah’s first visit to Meier’s hematology clinic. During most of the appointment Mylah colored at a desk in the corner of the examine room and the only audible sound from Mylah were her barrettes clicking together at the end of her braids. She is tiny for her age and underweight so it’s easy to underestimate her. But when the physician’s assistant asked about her medications, Mylah knew the answers and often chimed in before her mom could remember.

At the end of the appointment, Meier made plans for Mylah to see an ear, nose, and throat specialist in preparation for the tonsil surgery she’ll have before the end of summer break. And when Dr. Meier returns to Indianapolis, Mylah and her mom will have a hematologist to call when the pediatrician isn’t around.

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a news collaborative covering public health.