Illinois Tuition Law Helps Families, But Hurts Schools

As the Illinois Truth-in-Tuition law reaches its 10th year, experts say it helps families plan for college, but it makes it harder for public colleges to be strategic.

The law allows Illinois undergraduate students at public universities to attend school for four years without tuition increases. An amendment passed in 2010 extended it to six years, though allowing the school to increase tuition rates for fifth or sixth year students, as long as the price matches that of the students that came immediately after then.

Although the law provides some stability to students, it has hurt universities, according to Allan Karnes, accounting professor at Southern Illinois University Carbondale and member of the Illinois Board of Higher Education.

For example, when a university needs to increase tuition due to rising costs, inflation or decreasing state support, the incoming class has to shoulder the entire increase because their counterparts cannot pay higher fees.

‘It appears we’re raising tuition much more than we actually are, and so that cast us in a bad light,” Karnes said.

Moreover, the binding law requires public universities to guess what their budget will be for the next couple of years, said Thomas Hardy, executive director for media relations at the University of Illinois.

“It requires that the university take a bit of foresight in terms of where cost may go, and then reading a bit of a crystal ball, set tuition that will be fixed for a four year period,” Hardy said. “It locks us in for a four-year period.”

He adds that this comes at a time of decreasing state support. Since 2002, the University of Illinois has lost about $1 billion in spending authority, leading to tuition hikes and cuts. For example, the university shut down its Institute of Aviation in July 2011.

Having to predict future costs is also difficult, said Kinga Mauger, the bursar at Northern Illinois University. For example, the school did not expect the recession. Although the school faces rising costs, Mauger said it doesn’t want to simply ask incoming students to shoulder the burden. As a result, budgeting is far more difficult.

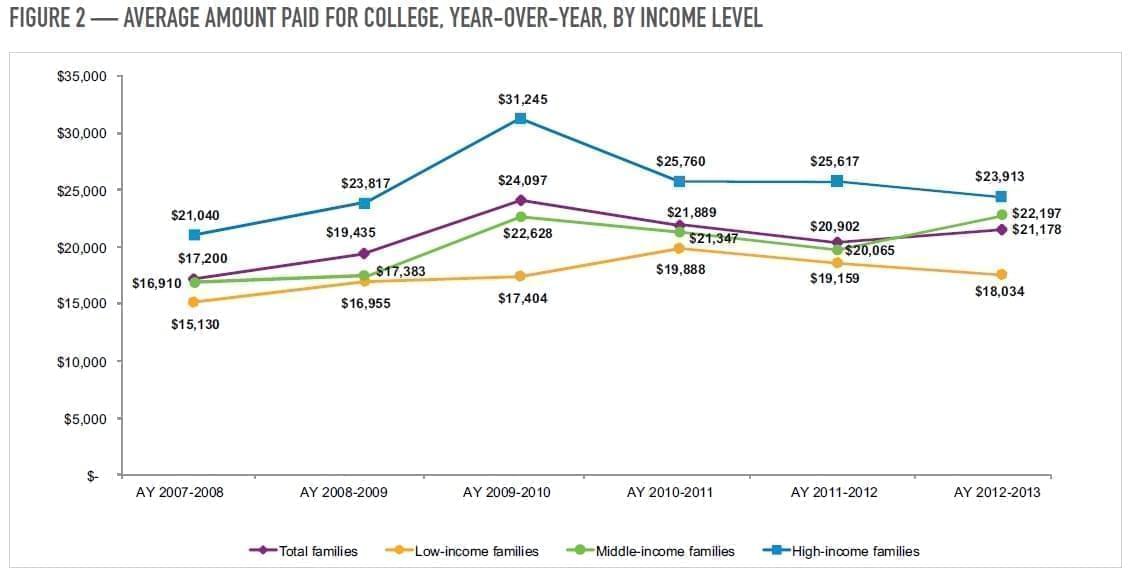

A new survey of 800 undergraduates and parents nationwide from student loan company Sallie Mae found that since 2010 and the recession, parents have paid less for college, relying more on loans, grants and scholarships. Overall, high and low-income families have paid less for college since 2010, but middle-income families have paid more.

Spending on college overall has fallen since the recession. That, along with the Illinois requirement to fix tuition for four years, makes budgeting difficult for state universities. (Sallie Mae)

Beyond Illinois, a federal Truth in Tuition proposal has been sent to a House committee.

It requires schools to give students a multi-year fee schedule upon admission, but allows for changes.

Karnes of the Illinois State Board of Education said lawmakers are not in the best position to draft tuition policies.

“There’s not a general understanding at that level (of) what the budgetary pressures are,” Karnes said. “Every school is different. We determine what tuition should be by what our costs are. We’re not trying to make money. We’re just trying to break even.”