Illinois Issues: The Prairie State’s Nuclear Waste Conundrum

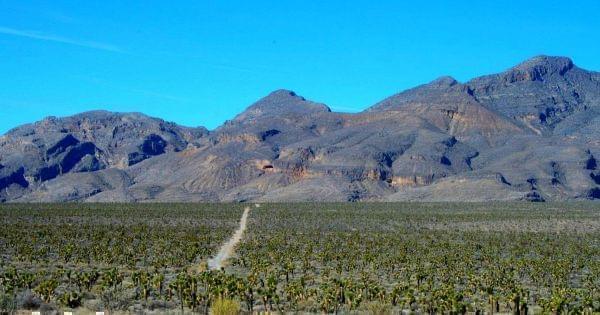

Yucca Mountain in Nevada, long considered by some to be a good site for nuclear waste storage, looms in the distance. Cyndy Sims Parr/Flickr

Under a federal measure passed 30 years ago, the spent fuel from America’s nuclear reactors is supposed to be permanently buried out in the Mojave Desert, tucked deep under a mountain, far from any population center and easily guarded.

In reality, though, that radioactive waste – tens of thousands of tons of it – is sitting in temporary storage at dozens of current and former nuclear power sites all over the country, as it has been for decades. The largest portion of it is divided among seven sites that dot the nation’s fifth-largest state: Illinois.

The nuclear power plant in Ogle County.

The story of how the Land of Lincoln became the nation's biggest de facto nuclear waste dump is a tale of public fear, political pragmatism and the power of NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard).

It’s a story that radiates political irony. Among those responsible for Illinois’ atomic dilemma is the state’s favorite son, Barack Obama, who scuttled a decades-old project that was to have created a national nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain, Nevada.

Now there is renewed hope that Illinois will eventually unload its nuclear burden after all, because President Donald Trump – who lost Illinois by more than 17 points in November – is moving toward reviving the Yucca Mountain project.

“I understand this is a politically sensitive topic for some,” former Texas Gov. Rick Perry, now Trump’s energy secretary, said in June, “but we can no longer kick the can down the road.”

It is perhaps fitting that Illinois is the epicenter of the American nuclear power industry today, given that the Atomic Era started here. In December 1942, at the University of Chicago, Enrico Fermi and Leo Szilard created the first artificial self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction.

That breakthrough, previously hypothesized from the work of Albert Einstein and others, would speed the end of World War II three years later, would hang ominously over the ensuing decades of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War, and would ultimately light the computer screen on which you’re reading this.

MW means megawatt.

Today, Illinois is home to six operational nuclear power sites, at Braidwood, Clinton, Cordova, LaSalle County, Morris and Ogle County. Together they operate 11 nuclear reactors currently in use, more than any other state.

The radioactive spent nuclear fuel from those reactors has remained in ostensibly temporary storage at each of Illinois’ operational sites – and at the now-shuttered Zion nuclear power plant on Lake Michigan – for years, as the federal government has failed to carry out its self-appointed responsibility to permanently dispose of it.

A revived Yucca Mountain project could change that. But not everyone believes it’s the answer to Illinois’ problem.

“For 35 years we have been watching the process disintegrate and become more and more politicized. Yucca Mountain was a political decision” rather than a scientific one, says Dave Kraft of the Nuclear Energy Information Service, a Chicago-based anti-nuclear power organization that cites the disposal issue as a fatal flaw of the nuclear industry.

Kraft’s group does favor the general concept behind the Yucca Mountain proposal — “deep geological permanent disposal” of nuclear waste — but argues that the chosen Nevada site is dangerously unsuitable.

To a broader point, Kraft cites the whole nuclear waste debate itself as further proof of what he claims is an untenable power source going forward. “Illinois has more nuclear generation than anyone else. We get all the benefits, but now we don’t want (the waste) in our backyard.”

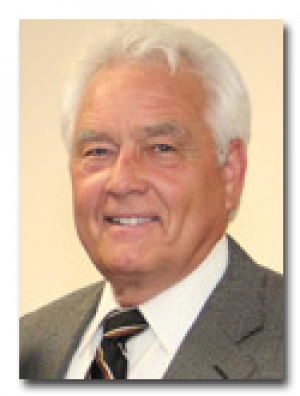

U.S. Rep John Shimkus, a Republican from Collinsville, supports a Trump administration plant to store nuclear waste at Yucca Mountain in Nevada.

At the other end of the debate is U.S. Rep. John Shimkus, a Republican from Collinsville. For years he has been a vocal proponent for getting the Yucca Mountain project back on track as a way to solve a nuclear waste conundrum that has been festering across America — especially in Illinois — while also aiding a nuclear power industry that faces a problem the federal government was supposed to have solved decades ago.

Shimkus points out that the Mojave Desert site “is nobody’s back yard.”

“That land mass is bigger than some of our New England states,” notes Shimkus. He sees it as a choice between putting the waste “in a location where it will be safe for a million years, versus a place that should be developed as lakefront property” — such as the shuttered nuclear power site at Zion.

THE SCIENCE

Nuclear energy is produced by fission — the literal “splitting of the atom” —within the controlled environment of a nuclear power plant. It is fueled by ceramic pellets that contain uranium and are sealed in metal tubes, called fuel rods. The nuclear reaction within the rods creates heat, which is used to boil water into steam, which drives turbines, which produces electricity.

Since the first nuclear reaction was achieved in the mid-20th Century, the promise of nuclear fission as a power source — its cleanliness in comparison to coal, its virtually inexhaustible supply — has come with a big asterisk.

The uranium fuel eventually loses its effectiveness in the nuclear reaction, and has to be replaced. The removed, “spent” fuel rods will continue to be dangerously radioactive for thousands of years. In addition to the health and environmental hazards, the waste contains materials that, in the wrong hands, could be weaponized. This stuff can't just go into a dumpster.

Ten “years after removal from a reactor, the surface dose rate for a typical spent fuel assembly exceeds 10,000 rem (a unit of radiation) /hour — far greater than the fatal whole-body dose for humans of about 500 rem,” explains a 2015 report by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission outlining the state of America’s nuclear waste issue.

The best solution, experts concluded decades ago, is to build a remote, impenetrable national repository where America's nuclear waste could be consolidated and contained, monitored and guarded in one place, essentially forever.

Conversely, the most dangerous situation, it is generally agreed, would be to allow that waste to simply remain on site where it was produced, at dozens of nuclear plants around the country — many of them near population centers, each one requiring endless vigilance, each one a potential environmental disaster or terrorist target.

And yet that's exactly where we are today.

Over the decades, U.S. nuclear reactors have produced some 79,000 metric tons of radioactive waste, a figure that grows by more than 2,000 metric tons every year. Most of it has remained in temporary storage in the same roughly 70 sites in more than 30 states where it was used, for the simple fact that there is nowhere else to put it. More than 10,000 tons of it resides in Illinois.

The waste is stored on site, first in deep-water pools made of thick reinforced concrete, where the spent rods — which initially are thermally hot as well as radioactive — can begin to cool. They are cooled for three to five years before removal to “dry cask” storage, in steel cylinders, surrounded by inert gas, welded shut and encased on concrete and other shielding.

As thorough as that storage might sound, the process never was meant to end there.

“Spent fuel storage at power plant sites is considered temporary with the ultimate goal being permanent disposal,” notes the U.S. NRC report. “However, at this time there are no facilities for permanent disposal of high-level waste.”

THE POLITICS

In 1954, Congress passed Atomic Energy Act, establishing the principle that the disposal of radioactive waste is the responsibility of the federal government. That was followed by the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982, creating a process to screen potential waste repository sites and establishing a Nuclear Waste Fund to pay for it, with fees on electricity.

Initially the government set out to consider numerous sites based on scientific suitability, but that notion quickly collapsed amid political wrangling in Congress. In a reversal of the usual battles between states vying to get federal projects, the fight this time was over who would be saddled with it.

Nevada lost that battle in 1987. For reasons that critics today still claim were more political than scientific, Congress that year amended the Nuclear Waste Policy Act to specify Yucca Mountain as the only site under consideration for creation of America’s one official high-level commercial nuclear waste disposal compound.

For the next two decades, the process of planning the repository and (briefly) beginning its construction lurched slowly along, with the federal government spending $11 billion to get the project off the ground and the state of Nevada suing all along the way to stop it. By the end of George W. Bush’s presidency in January 2009 — a decade after the original planned opening of the Yucca Mountain national nuclear waste site — all that had been completed was a single five-mile exploratory tunnel.

Eight years later, that remains all there is.

Then Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid talks with former President Barack Obama in 2010.

Obama’s administration gave myriad technical reasons for cutting off funding to the Yucca Mountain project almost immediately upon coming into office, but the unspoken reason wasn’t hard to surmise: Obama’s chief ally in Congress, Senate Democratic leader Harry Reid of Nevada, also happened to be the project’s most vociferous opponent.

Obama's decision, while popular in Nevada, drew howls of protest from the national nuclear industry and from states with nuclear power plants. The Wall Street Journal declared it “a crude political bargain in which Reid agreed to do the President’s dirty work on Capitol Hill if Mr. Obama blocked the nuclear waste depository.”

If that deal solved a problem for Nevada, it created one for those dozens of other nuclear states. With the Yucca Mountain project suspended and nothing offered in its place, states that had nuclear waste piling up at its nuclear reactor sites had to continue storing it there.

ZION’S DILEMMA

The now-shuttered Zion nuclear plant in 1974.

In Illinois, the shuttered nuclear power plant at Zion illustrates the complexity — and the daunting longevity — of the problem.

The Chicago-area plant on the shore of Lake Michigan shut down permanently after an operator-error mishap in 1997. Twenty years later, its spent nuclear waste still is stored on site because of the lack of a national repository for it.

The loss to the local community of the jobs and tax base the power plant had supplied have driven up property taxes and driven down the housing market. Meanwhile, the lakefront land remains unusable for redevelopment into anything other than what it is now: a nuclear waste dump.

“When the plant was built, we understood there was going to be an eyesore, we would lose use of the lakefront … The tradeoff was that we received a significant amount of tax dollars, and there were a lot jobs,” Zion Mayor Al Hill says. “The deal was, when this was done, the (lakefront land) would be brought back to its previous state and the plant would be gone.”

It hasn’t worked out that way.

“Without Yucca Mountain, the nuclear fuel rods are just sitting there (in dry cask storage), and there’s no end in sight,” Hill says. “The deal never was that we were going to store spent fuel rods in our community. That’s the federal government’s responsibility.”

Based on that argument, Zion and about a dozen other communities around the country with shuttered plants – towns that have lost the economic benefits of a power plant, but still are saddled with the waste because there is nowhere to move it – have sought federal legislation to compensate those towns in federal dollars. The effort hasn’t yet succeeded but is continuing.

Aside from the economic issues, Hill said, there are intangible costs to having 2.2 million pounds of nuclear waste in town, within a mile of houses, surrounded by security fences and armed guards.

“There’s an effect on the psyche of the town, having those spent fuel rods here. It’s unnerving,” he says. “We want them out. We don’t care where they go. And until they’re moved, we think we should be compensated.”

‘SCREW NEVADA’?

For Zion and other communities wrestling with that waste, the light at the end of the proverbial tunnel could start with that literal tunnel — the unfinished one in Nevada. The Trump Administration's proposed federal budget contains $120 million to restart development of a permanent national nuclear waste site at Yucca Mountain.

Nevada Gov. Brian Sandoval meets with U.S. Energy Secretary RIck Perry in April.

“We have a moral and national security obligation to come up with a long-term solution,” Perry, Trump’s energy secretary, told a House Appropriations subcommittee in June, in which he called the resumed development of Yucca Mountain a top priority.

Not surprisingly, Nevadans are viewing the latest twist with some trepidation. In an editorial in June, the Las Vegas Review-Journal called the Yucca Mountain project “a multibillion dollar boondoggle.”

“The pre-ordained process that resulted in its selection as the nation’s lone nuclear waste repository was a sham designed to target a small state with minimal political clout,” alleged the paper.

Still, the editorial hesitantly suggested, it might be time to accept the turning tide, stop its “reflexive opposition” and explore whether a deal can be forged that brings to Nevada education dollars, new infrastructure or other federal perks.

The paper noted that the original legislation was dubbed by its opponents the “Screw Nevada bill.”

The Chicago Tribune, in an editorial in April, noted that as well, concluding: “We hope the Trump administration and Congress will revive it. Because if they don’t, we’re all screwed.”

Kevin McDermott is a political reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Links

- In Rick Perry Energy Hearing, Questions Likely On Nuclear Security, Environment

- Economic Growth For Clinton Means More Than Keeping A Nuclear Plant Open

- Bill Raising Electric Rates To Help Clinton, Quad-Cities Nuclear Plants Heads To Governor’s Desk

- Exelon/ComEd Offers Compromises In Nuclear Plant Legislation Talks

- Exelon to ‘Move Forward’ On Closure Of Clinton, Quad Cities Nuclear Plants

- Rauner & Area Officials To Meet To Discuss Exelon Proposal To Protect Clinton, QC Nuclear Plants

- Illinois Issues: The Battle Over Transparency And Privacy In The Digital Age

- Illinois Issues: Local Icon Shifts To ‘The Most Dangerous Woman In America’

- Illinois Issues: Legislative Checklist

- Illinois Issues: What’s It Gonna Take To Get A Budget?

- Illinois Issues: Officials Wage War Against Hate

- Illinois Issues: State Marches Toward Clean Energy