Illinois Issues: State Prison Population Is Down 20 Percent — Who Gets Credit?

Stateville Correctional Center in Joliet, Illinois. Illustration of Apple Maps image by Brian Mackey/NPR Illinois

The driving question here is: Who gets to take credit? We'll come back to this in a couple minutes.

But first, it’s important to understand the context in which Illinois began locking up more and more of its citizens. The numbers began inching up in the 1970s — after a decade of political assassinations, bombings, hijackings, and garden variety street crime.

The late Gov. Dan Walker argued for change in his final State of the State address, in 1976.

“The sentencing and parole system that we now have in Illinois and throughout the nation is a dismal failure, Walker told members of the General Assembly. “It does not deter, it does not punish, it does not rehabilitate and it should be scrapped.”

In the years that followed, Republican governors and Democratic legislators teamed up to lengthen prison sentences. There was also the war on drugs, and a building boom in prisons, which were seen as sources of good jobs in downstate communities abandoned by industry.

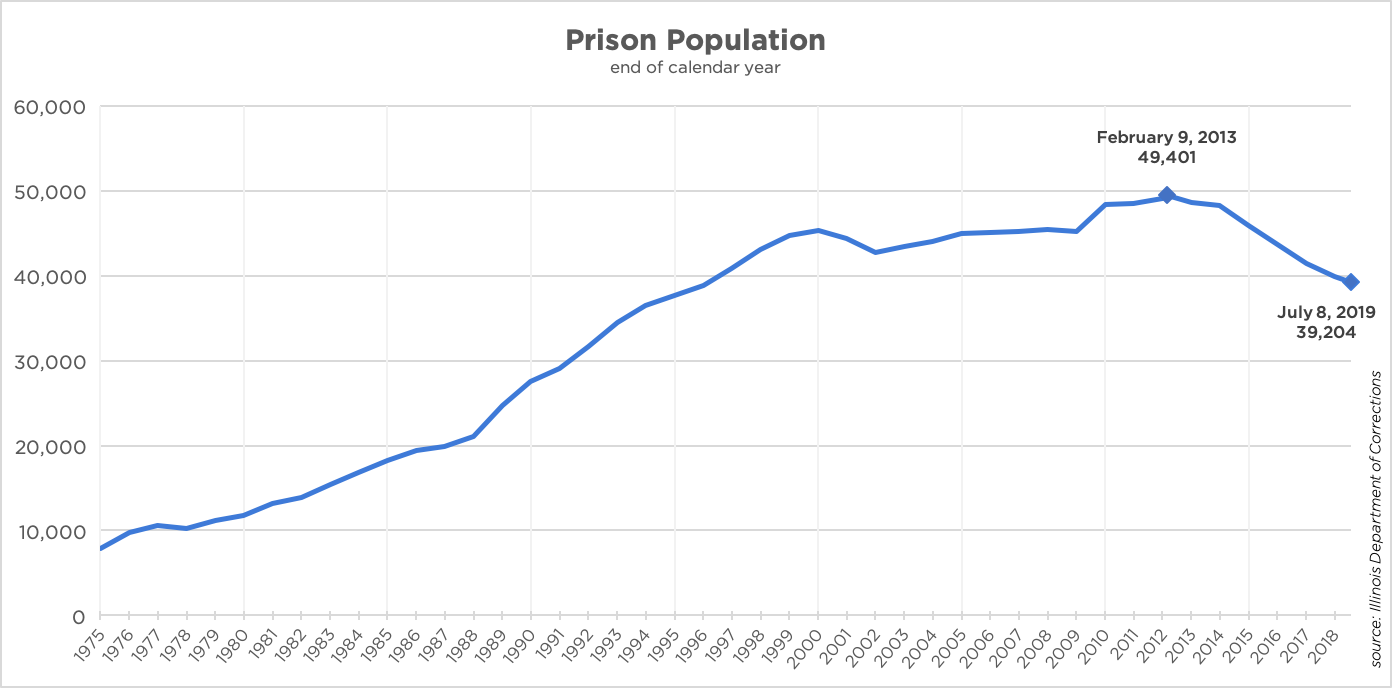

The population doubled in the ’80s — and doubled again in the ’90s. The number peaked on February 9, 2013, when 49,401 people were locked up. Projections had it going even higher.

But that's not the way things worked out. The numbers began to drop, gradually at first, then more quickly, until late last year, when the population dipped below 40,000 for the first time since the late ’90s.

The Illinois prison population from 1975 to the present. The population number is based on the final day of each year listed.

The question is: Why?

“I think it’s important to recognize that the idea that there’s a single state policy that guides prison utilization isn’t really accurate when you think about how the justice system is organized and functions,” said David Olson. He’s a professor of criminology at Loyola University Chicago, where he’s also co-director of the Center for Criminal Justice Research, Policy and Practice.

Olson says there’s no one policy because of how decentralized the criminal justice system is in Illinois — 800 police departments, 102 separately elected state's attorneys, hundreds of judges.

So when the police chief in Dixon sets up a program where the drug addicts can turn themselves in for treatment instead of jail — that makes a little difference. For larger-scale change, you have to go to the places that send the most people to prison: and that means Chicago and Cook County.

Olson says the city has seen an 80 percent drop in felony drug arrests over the last decade. In fact, a significant part of the statewide prison decline can be traced back to just three Chicago police districts.

“And that’s really been concentrated in specific neighborhoods, just like the tripling and quadrupling of arrests in Chicago in the late ‘80s tended to be concentrated in very specific neighborhoods,” Olson said.

Another significant drop is connected to retail theft. In 2016, nearly a thousand people were in prison for the crime. By the end of last year, that number was cut in half. In between, Cook County got a new prosecutor by the name of Kim Foxx.

“The number one charge in 2016 that we were prosecuting was not guns, was not shootings. It was retail theft,” Foxx said in an interview she gave last year with Chicago public radio station WBEZ.

It’s pretty easy for an Illinoisan to get retail theft up to a felony prosecution — all they have to do is steal more than $300 worth of stuff. That’s a significantly lower threshold than a lot of states.

But even though the law had not changed, Foxx directed her lawyers to act as though it had. From then on, retail theft would only be charged as a felony if more than a $1,000 worth of stuff was stolen.

“Some of the people that we were seeing repeatedly were not people in sophisticated retail theft rings,” Foxx said. “We saw people who were stealing because they were either homeless, had addiction issues, had mental health issues, poverty-related issues, and (were) not threats.”

This reminds me of something a criminal justice reformer once told me. He said prison should be for the people you’re afraid of, not the people you’re mad at.

Returning to Olson, the Loyola criminologist, that’s the effect of what’s happening. He says the population that remains in Illinois prisons consists of people convicted of more violent crimes. They’re also older.

And both of these realities have consequences.

On the one hand, if people are staying longer, there’s a greater opportunity to provide them with rehabilitative services, like drug treatment or anger management counseling. On the other hand, older prisoners have more health problems, and are thus more expensive than younger inmates.

And for the people who’ve avoided prison — Olson says they’re not necessarily free either. Many are being sentenced to probation.

“There still is this concentration of people under the custody of the criminal justice in specific communities,” Olson said.

Even so, the 20 percent drop in the prison population is remarkable. Which brings us back to the question we started with: Who gets credit for the turnound?

“Everybody can have a little piece of the action,” Olson said. He already talked about police and prosecutors. He says the legislature has contributed, and the Department of Corrections is trying to improve how it treats inmates, which leads to better outcomes. And then there’s you.

“The electorate now is more willing to allow for prison to not be the primary response behind crime,” Olson said. “So everybody can take a little bit of credit, but if something goes bad, everybody will say ‘it’s not my fault.’”

Some things, it seems, never change.

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlines to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by NPR Illinois in Springfield.