Illinois Issues: Budget Impasse May Prove Setback To Governor’s Prison Reduction Goal

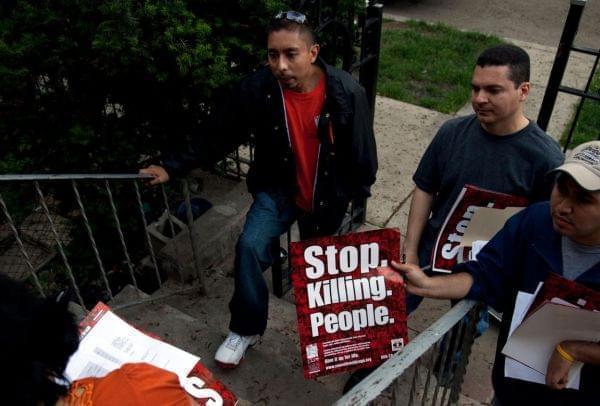

CeaseFire Illinois workers conduct outreach. CeaseFire Illinois

Soon after taking office, Gov. Bruce Rauner set a goal of cutting Illinois' prison population by a quarter over the next decade. But the current budget crisis has cut off funding for programs that could be key to meeting his target.

As the 2014 Illinois governor’s race came to a close, Frederick Seaton was nervous. Seaton was in his ninth year working for CeaseFire Illinois. The program deploys neighborhood residents, including some former criminals, to monitor and prevent gun violence. As supervisor of a CeaseFire site in Chicago’s West Garfield Park, Seaton’s salary — and those of the nine employees he oversaw — were dependent on a state grant. But Bruce Rauner, then the new governor-elect, hadn’t specified whether the spending cuts he’d promised on the campaign trail would affect CeaseFire’s funding.

“We kind of knew there was going to be some big changes,” Seaton says. “But we were shocked as to the magnitude of the changes.”

Today, with no state budget, funding for crime and recidivism prevention programs has been cut off nearly a year — or in CeaseFire’s case, even longer. Specialized courts and probation offerings meant to keep nonviolent offenders out of prison are struggling to stay afloat or folding altogether. Many worry that the failure to fund these programs has proved a critical setback for an administration that seeks to substantially, and quickly, reduce state prisoner populations.

Rauner Cuts CeaseFire Funding, But Sets Prison Inmate Reduction Goal

In mid-February 2015, the freshly inaugurated governor put forth a budget for the next fiscal year. He proposed to slash CeaseFire’s state funding by sixty percent, from $4.7 million to $1.9 million. But even amid the bad news, CeaseFire employees saw reason for hope. The week before, Rauner had issued an executive order calling on the state to reduce its prison population by 25 percent by the year 2025 — a reduction of some 12,000 prisoners. The order also established a commission to decide how best to achieve that lofty goal. “I remember feeling encouraged that we weren’t zeroed out, just cut, which gave us a chance to prove ourselves,” says Kathy Buettner, a spokesperson for Cure Violence, the organization that oversees CeaseFire Illinois.

Two weeks later, that last sliver of optimism would evaporate. The University of Illinois, which administers CeaseFire Illinois, received a letter stating that their state grant for CeaseFire was suspended, effective immediately. At the time, Rauner was looking for ways to close a $1.6 billion shortfall for the 2015 Fiscal Year.

That grant had been financing upwards of 85 percent of the program. Shortly after the letter, more than 100 staff members were laid off. Within two months, the majority of CeaseFire’s 24 sites across the state had closed. Seaton’s West Garfield Park site managed to stay open through July, operating on a shoestring budget.

Since the site closed, Seaton has been working multiple part-time jobs, and continues fighting gun violence on a volunteer basis. When he hears about a situation that’s likely to spur a shooting, he contacts his former staff members to see whether they can help intervene. “I can get one or two guys,” says Seaton, whose former employees still call him ‘Supe,’ short for ‘supervisor.’ “I can’t get the whole team out, because everybody has to eat.”

While he estimates that his team has managed to intervene in more than two dozen such scenarios over the last ten months, Seaton has no doubt that the CeaseFire site’s shuttering has led to more shootings in the neighborhood.

But determining the precise impact of a CeaseFire site — or its closing — is far from simple. Gun violence has increased considerably across Chicago in recent months. The Chicago Tribune reported this week that the number of people shot in the city is 50 percent greater than what it was at this time last year. And summer, the season when violence typically spikes in Chicago, hasn’t even begun.

But increases in shooting can also been seen in cities like Dallas, Las Vegas and Los Angeles, which have never implemented CeaseFire sites, suggesting that other factors may be at play.

Impact Of CeaseFire Illinois & Other ARI Programs

In 2009 a team of researchers from Northwestern University looked at seven long-running CeaseFire Illinois sites, and found that the program was responsible for decreasing shootings by as much as 28 percent in some neighborhoods. But when the same report examined the summer of 2007 — when a previous state budget impasse had forced most CeaseFire sites to close their doors for several months — it “did not reveal any dramatic shifts in crime following the closings.”

In the absence of state money, the five active CeaseFire Illinois sites, which are clustered in the city of Chicago, are now being supported by foundations, corporations and private donors.

CeaseFire is perhaps the best-known state anti-crime program. That’s thanks in part to media coverage, such as the 2011 documentary film “The Interrupters,” which followed three CeaseFire violence interrupters for a year. The program could help with the governor’s goal by preventing gun crimes and keeping those who might have ended up in the state’s prisons — possibly for long sentences — from breaking the law in the first place.

But prior to the budget impasse, there was mounting interest in programs that focus on rehabilitating people who have committed crimes without sending them to prison.

Adult Redeploy Illinois (ARI) began in 2011 and provides county and circuit courts with state money to divert nonviolent offenders from incarceration. In its first three years, the program grew to 20 sites statewide, which varied from drug and mental health courts, to special tracks for veterans, to supervision and cognitive therapy for those sentenced to probation. Rauner, in his first State of the State address, applauded the program, and his proposed 2016 budget sought to shift much of CeaseFire’s funding to ARI.

Between January 2011 and December 2014, reports from ARI claim that the program diverted over 2,100 individuals from the Department of Corrections. With an average per capita prison cost of $21,500 per year (during that time frame), the program estimates it saved the state a total of $46.5 million on prison expenses in that same period. But the benefits extend beyond immediate cost savings.

By keeping people out of prison, experts say that ARI reduces the odds that an offender will commit another crime later. “For most people who are being sentenced to prison, the reasons for their involvement in crime are not being addressed,” says David Olson, professor of criminal justice and criminology at Loyola University Chicago. “So in order to actually change someone’s involvement in criminal activity, we have to do more than simply punish them.” Illinois’ Sentencing Policy Advisory Council (SPAC) finds that 48 percent of those incarcerated in the state end up returning to prison within three years of release. And when social costs are taken into account — things like foregone wages, medical bills and victims’ pain and suffering — SPAC puts the total cost of one such recidivism at $118,746.

The Kane County Example

One successful ARI program was established in Kane County. In 2010, the county had become concerned that some 16 percent of individuals it was sending to prison were coming out of the probation system. Many of them weren’t committing new crimes, but simply getting technical violations, or failing to meet the terms of their probation, according to Lisa Aust, executive director of Court Services for Kane County. “They’d get a couple of technical violations, they’d get in trouble with the court and they’d never recover from that,” Aust says. For instance, a probationer might incur one violation for failing a drug test, another for failing to complete substance abuse treatment, have their probation revoked and end up being sentenced to prison — the very outcome that their probation was supposed to prevent.

With this in mind, Kane County submitted a proposal for an ARI grant, which they received in October 2013. The idea was to help prevent the downward spiral, particularly among those with problems that made technical violations more likely, like mental health issues or lack of housing. The state provided the funds with the expectation that the county keep 25 percent of ARI program participants out of prison over the next 12 months.

Roughly half of the $647,752 that Kane County ARI received over the next year and a half was used to hire three specialized probation officers who had received special training in mental health and cognitive behavioral therapy. They received small caseloads, allowing them to closely supervise the ARI participants. The other half of the funding financed substance abuse treatment for those who struggled with drug use, and temporary housing for those who were homeless or transient.

The ARI team also made a point to celebrate clients’ progress. A wall covered in brightly colored paper served as a makeshift hall of fame called the Wall of Wow, says LaTanya Hill, deputy director and program manager at Court Services for the county. “And if something had happened that was very positive or they had done something really well — they completed treatment, or they came to a certain number of appointments, or they got a job, something like that — their name and accomplishment was written out on a Post-It and put on the Wall of Wow,” recalls Hill.

Aust says the county had sent 112 probationers to prison in 2012 and 82 in 2013. “And then in 2014, we only sent 30 people to the Department of Corrections off of the probation caseload for violating,” she says — a reduction well above the 25 percent yearly goal. “That’s a remarkable drop, if you ask me.”

Kane County received its last payment from the state in June 2015, but managed to continue funding its ARI program fully through October of last year, using probation fees to sustain the program until a budget was passed. By November, it was clear that a budget was not coming. “We laid off the staff, tried to have our regular probation officers do the supervision for these clients and just maintain treatment,” Hill says. But with probation officers unequipped to address clients’ needs, the program was losing fidelity to its original model. “Finally, in December, we decided that we had to terminate the program itself,” says Aust.

To date, Kane County is the only ARI site that has folded as a result of the budget impasse. Across the state 20 ARI sites continue to provide services to 38 counties, supported by funding at the county level. But much of that funding will not continue indefinitely.

To keep its ARI program afloat, Will County redirected $200,000 intended for its drug court and borrowed $75,000 from the county finance committee — however, the committee has made clear that if a state budget is not passed by June 30, the program may have to shut down.

Cook County runs the two largest ARI programs, with state budget allocations totaling nearly $2 million. The county has been fronting the cost since the impasse. But unless it starts seeing the money the state owes, Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle has warned, ARI will be drastically trimmed or eliminated. Both programs have already made significant cuts to staff and spending. “Every day that we’ve gone without a budget is a day that people wonder whether the program is going to be shut down,” says Katy Welter, project manager for Cook County Access to Community Treatment Court, one of the two ARI programs.

The ARI model was adapted from Redeploy Illinois, a program intended to divert at-risk juveniles away from system. The juvenile program, which once covered most of the state, has also felt the strain. Three of the 13 area sites have been dismantled since the June, and most others have had to cut some services, ranging from transportation to recreational activities to psychological evaluations. But Marianne Manko, spokesperson for Illinois Department of Human Services, which administers Redeploy Illinois, says that most counties have stepped up to ensure that the programs will continue. “There’s been rumors that other [sites] are going to be shutting down, and they’re not,” says Manko. “We’ve been really lucky.”

Uncertain Future For ARI Programs

The failure to fund Redeploy is almost universally frustrating. The program has been openly supported by everyone from Rauner to the ACLU to limited-government proponents like the Illinois Policy Institute’s Bryant Jackson-Green, who heralded ARI as a shining example of “cost-effective criminal-justice reform.”

Add to that list the Illinois State Commission on Criminal Justice and Sentencing Reform, which was created by Rauner though that same executive order that calls for a reduction in the prison population. The commission released a report recommending that the state divert certain offenders from prisons and offer rehabilitation when possible. But the more people who are incarcerated because of the impasse, the fewer resources are available to keep others from meeting that fate. “For those who really do need a more intensive therapeutic intervention, we’re spread too thin,” says Loyola University Chicago’s David Olson, who serves on the Commission. “We don’t have the resources to respond to their needs.”

Even if a state budget is enacted soon, it’s not clear when ARI sites will manage to get back on track toward their 25 percent reduction goals. In 2015, Kane County, which spent half of that year with a reduced ARI program, sent 39 probationers to prison — a 30 percent increase from 2014. Year-to-date totals for 2016, however, do not show any increase after the program was dismantled and and overall. Overall, the headcount in the Illinois Department of Corrections was down in the department's most recent quarterly report, which measured the population as of November 30, 2015.

Nevertheless, Aust says the budget impasse has rippled through her county, hurting the social services her program depended on. Halfway houses have closed their doors. The Ecker Center for Mental Health, the primary mental health clinic for the north end of Kane County, is no longer accepting new clients. “I don’t want to be all doom and gloom, because we’re trying our best,” says Aust. But after nearly a year without state funding, she’s stopped trying to plan for what happens after the budget impasse. “I haven’t even let myself think about it.”

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlines to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by public radio station WUIS in Springfield.