Illinois Facing Most Severe Erosion In Two Decades

Erosion-causing rain in the Midwest is going to come down harder and more often as the climate changes. Illinois farmland is already losing an unsustainable amount of soil, and environmentalists are raising the alarm. Lynn Betts / USDA

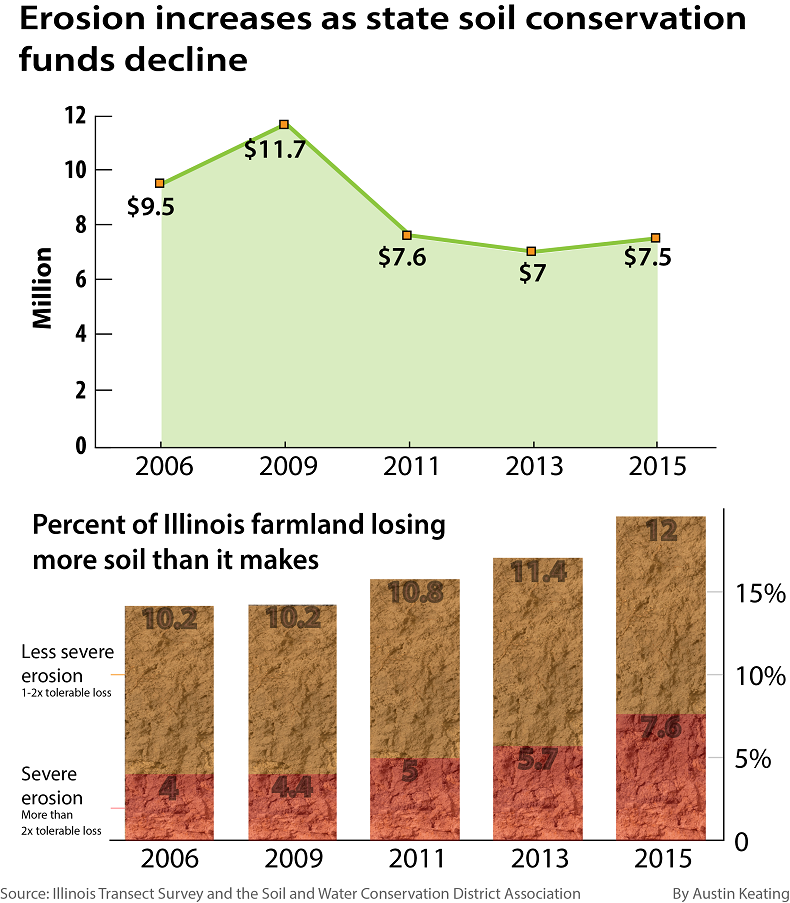

Illinois is losing topsoil – the layer of surface dirt that’s rich with nutrients and vital for food production. And the problem of erosion on Illinois farms is serious: In 2015, roughly one-fifth of Illinois’s farmland lost more soil than it made.

Editor’s note: If you want to really dig in to soil loss, check out the annotated version on the reporter's website. If you want the quick and dirty, listen to the audio version, a Q and A with the reporter.

When retired Champaign County Resource Conservationist Bruce Stikkers first came to Central Illinois in the ‘70s, he remembers seeing mounds of mud in roadside ditches following the heavy spring rains. In the winter, dirt would blow like snow.

He says an older tilling technique involving what's called a Moldboard plow was the culprit. The plow would cut deep into the soil, loosening it so much that the elements could cart it off with ease.

“Now no one uses them. There is a lot less soil erosion than what there was, but we’re still not perfect by any means,” he says.

“Not perfect” may be putting it mildly. The most recent data from the Illinois Department of Agriculture shows roughly one-fifth of Illinois farmland is losing soil.

The immediate consequences of erosion include lower-yielding crops and damage to the environment. And the long-term consequences could be more severe, as the continued loss of soil over the next several decades could eventually convert farmland into infertile ground. Both soil conservationists, environmentalists and farmers agree something needs to be done to rein in erosion before it’s too late. But they disagree on what constitutes the best path forward.

Soil basics

Soil is considered by scientists to be a non-renewable resource, because although it can be created—from decaying plant material and the slow, geological breakdown of minerals—the process is extremely slow. Some scientists estimate it takes about 100 to 1,000 years to make an inch of top soil from these natural processes.

Overall, we’ve lost about half of the organic matter that we had when we started plowing ... In terms of tons of soil lost, that is a lot.”Jennifer Filipiak, associate Midwest director at American Farmland Trust

Illinois has some of the most fertile soil in the world, a result of thousands of years of year-round prairieland and the minerals left behind by prehistoric glaciers. But the introduction of modern agriculture techniques resulted in the replacement of prairie with farms that grow annual crops—leaving fields bare for much of the year.

This lack of a prairie “mat” coupled with tilling—the common practice of loosening the soil to enable roots to sprout more easily—has made soil vulnerable to harm by rain and wind. Hilly lands, prevalent in southern regions of Illinois, are most susceptible to losing soil as rain runs faster down slopes than flatter land, carrying more soil with it.

The amount of soil loss to date is stark, says Jennifer Filipiak, associate Midwest director at American Farmland Trust.

“Overall, we’ve lost about half of the organic matter that we had when we started plowing,” she says, referring to the portion of soil created from decaying plant matter. “In terms of tons of soil lost, that is a lot. It’s really a lot. I couldn’t even wrap my head around it.”

When a farm loses more soil than it’s made, it experiences what the agricultural industry refers to as “above tolerable soil loss.”

According to a recent survey, 7 percent of Illinois farmland has twice the amount of soil loss considered "above tolerable," the same as was the case in 1994. Twelve percent is between one and two times the tolerable soil loss level, which represents a 25 percent decrease since 1994, but still at the highest it has been since at least 2006.

The survey has been conducted by the Illinois Department of Agriculture every other year since 1994. It involves sending resource conservationists like Stikkers to check hundreds of transects, or survey points, through their windshields, and was started to track Illinois’ progress away from excessive soil loss.

Through public outreach and cost-share programs carried out by Soil and Water Conservation Districts – and time – the hope was erosion could be reined in without government regulation, Stikkers says.

For each point, resource conservationists determine how much residue is left on the field from harvest, and look through a spreadsheet to see how much erosion that residue level results in for the type of soil. It’s not a perfect survey—one study in Iowa found that a similar technique didn’t account for gully erosion, which under a new modeling method, resulted in as much as $1 billion in losses for Iowa’s agriculture.

Michelle Wander, a professor at the University of Illinois, says that since yields for conventional crops have skyrocketed with increased inputs, and genetic and mechanical improvements, the loss of yield from erosion has been “masked.”

“Back in the early 20th century, we were the first country to set a soil conservation agenda. We were losing too much, and we weren’t making it up with these improvements you’re seeing now,” she says. “But it’s still happening, and it’s really quite severe.”

Percentage of farms that lost more soil than was made in 2015

Why it matters

Department of Agriculture Soil Scientist Roger Windhorn says Illinois won’t be hitting bedrock anytime soon with the soil loss rates he sees. However, erosion does mean lower yields on farms that have it, and lower yields for farmers who inherit or buy the land for years down the road. That translates into less revenue for local governments, since property taxes for farmland are based on potential yield.

Erosion also leads to reduced water quality downstream. Phosphorus fertilizers cling to soil particles and make their way into water sources. The sediment often settles at the bottom of a waterway, and if it’s particularly shallow, or the sediment builds high enough, the sun can bake the phosphorus and cause an algal bloom. Many of these blooms make the water harmful for human consumption and recreation.

The sediment itself also reduces the amount of water a body of water can hold. The City of Decatur in central Illinois is in the process of a $90 million dredging project to increase the volume of their lake to keep it stable during droughts.

Craig Cox of the Environmental Working Group added that erosion needs to be reined in now because climate change is going to make erosion more severe. Winds in the Midwest are expected to pick up by 2 percent by the end of the century, and rainfall is expected to increase, bringing a projected 30 to 274 percent rise in erosion, according to one study.

Ironically, soil is one of humanity’s best chances to reduce emissions and slow climate change. Plants take in carbon dioxide and store it in the ground, making them what scientists call carbon sinks – but when a farmer tills, much of that carbon is released into the atmosphere. If every country in the world built-up its soil organic carbon by .4 percent each year, the world would lock-away 75% of the greenhouse gas annually. France has signed up for this goal, but so far the U.S. has not.

Layer one: funding for soil conservation has declined for 8 years

Layer two: Environmentalists say not enough farmers are adopting soil conserving practices

Nils Donnell trouble shoots a problem with a strip tilling rig. Strip tilling is where a farmer tills in narrow strips, and comes back in the Spring to plant over them. Between all the strips are 30-inch-wide regions of undisturbed soil, making it one of the most soil friendly options available to farmers.

Layer 3: Farmers of highly erodible fields aren’t being held accountable

It's always been my thought that I want to pass the ground on to the next generation as good as, if not better as, when I got it.”Mark Donnell, farmer