How Scientists Are Partnering With Indigenous Communities For Genomics Research

Johns Hopkins post-doctoral researcher Dr. Jessica L. Elm, citizen of the Oneida Nation and descendant of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of the Mohicans, watches Alison Watson of the Navajo Nation as she receives hands-on training in genomics research at the 2019 SING workshop taking place on the University of Illinois Urbana campus. Courtesy of Rene Begay/SING workshop

Many scientists are interested in studying the DNA of Indigenous populations in an effort to reveal the "human migration story" and contribute to our understanding about the genetic basis of disease.

But many in the Indigenous community feel these scientific pursuits have a history of being exploitative, achieved without consideration of the needs or interests of the people who have contributed their DNA for science.

The result is a lack of trust between Indigenous people and scientists, said University of Illinois anthropologist Ripan Malhi.

“There's a long history (of) anthropologists and scientists going to Indigenous communities, getting what they need, leaving and never coming back,” Malhi said. “I learned early on that that was the norm in science and anthropology up until recently.”

Ripan Malhi is an anthropology professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

He said he decided to launch the SING program in 2011 in an effort to change that.

SING, which stands for Summer Internship for Indigenous People in Genomics, brings together 15 to 20 Indigenous scientists and members of their communities every year for a week of hands-on training in genomics—the interdisciplinary field of biology focused on the study of an organism’s complete set of DNA.

The training equips them to bring the tools of genetic research to their communities, which can help facilitate partnerships based on trust between researchers and Indigenous people.

This year’s event is taking place this week at the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology in Urbana.

“We discuss all week about genomics, how it can be used as a tool and how it may fit or not fit with Indigenous ideas and knowledge,” Malhi said. “We have discussions on how to decolonize science, and then we do a large number of discussions about ethical, legal and social implications of research with Indigenous communities in genomics research.”

Since SING launched, Malhi said more than 120 participants have received hands-on training in genomics, including Krystal Tsosie, a doctoral student at Vanderbilt University.

Krystal Tsosie is a Navajo geneticist and bioethicist at Vanderbilt University.

Tsosie, who is a descendant of the Navajo Nation, attended the first-ever SING workshop in 2011 and is now one of the organizers.

“SING has been influential in training the next generation of Indigenous scientists, so that we can ensure that science is done by us, for us, and truly benefits us,” said Tsosie.

Tsosie said participating in the SING workshop over the years has helped her feel less isolated as an Indigenous scientist.

“In terms of graduate students, and especially those in STEM fields, I think I'm pretty much the only (Native American student) at Vanderbilt University,” she said. “So, getting that sort of sense of community from my Indigenous peers, who are undergoing the same sort of challenges in academia, is great.”

SING alumni and faculty have also worked to publish ethical guidelines for scientists on how to approach genomics research in a way that is sensitive to the interests of Indigenous people and can benefit their communities.

Other countries, including Canada and New Zealand, have launched SING programs. Malhi said Australia will host their first-ever SING workshop later this year.

This year’s program at the U of I involves 18 participants from tribal nations across the U.S. and the First Nations of Canada. Most of the 19 faculty members leading the training are Indigenous, and others are non-Indigenous allies from institutions in the U.S., Canada and Mexico.

Malhi said he has changed the way he approaches his research in anthropology and now seeks to work in partnership with Indigenous communities.

“I work with the communities to figure out what they want to study, as well as what we want to study, and basically partner with them,” Malhi said. “And after collecting what I need, with DNA samples, I come back, get results here in the lab. And then I go back annually to report the results to the community and figure out the next steps.”

Tsosie said this kind of intentionality is critical to ensuring researchers don’t overlook the needs and interests of the Indigneous communities they’re studying.

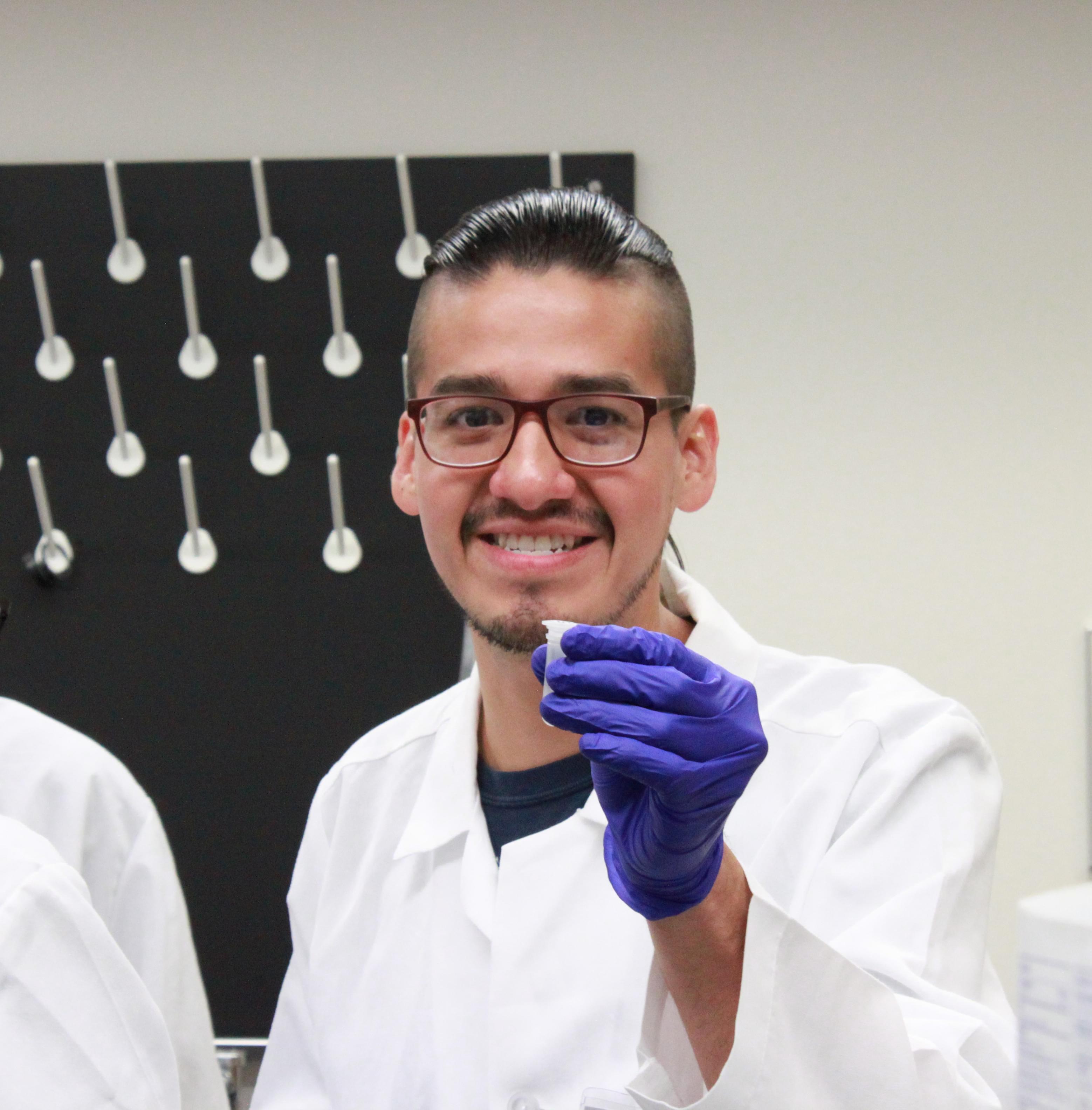

Duke University Ph.D. candidate Raymond L. Allen (Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians) holds up a spin column as part of the protocol to isolate his own mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) at the 2019 SING workshop.

As a geneticist and bioethicist, Tsosie studies preeclampsia, a pregnancy complication, among pregnant Ojibwe women in northern North Dakota. She also studies how environmental factors contribute to disease among Indigenous communities in South Dakota.

She said she takes steps to engage members of the Indigenous communities and include them in the research process.

This helps ensure that the research is “equitable within our communities, to ensure that genomics research that involves Indigenous people will actually benefit us, as opposed to just using us as subjects (like) in the past,” Tsosie said.

Follow Christine on Twitter: @CTHerman

EDITOR'S NOTE: The opening paragraphs of this story were revised to reflect the how the rights of Indigenous people have historically not been considered in this pursuit of scientific research.

Links

- Former U of I Prof Joy Harjo Becomes First Native American U.S. Poet Laureate

- Dedication Of Wassaja Hall Honors U Of I’s First Native American Graduate

- A New Native American Face on Campus

- Dee Brown And Media Depictions Of Native Americans

- After Identity Politics: Race, Disability, and the New Genomics

- Post-Genomics and the Concept of Race in Science: Tensions, Contradictions, and Resolutions