Help Or Hinder? Federal Agencies At Odds Over Biofuels

The University of Illinois Energy Farm is situated on 320 acres just south of Urbana. Crops of all kinds and shapes are grown for research, including sugar cane in a greenhouse and many kinds of miscanthus grasses out in the field. Madelyn Beck/Harvest Public Media

Scott Pruitt’s resignation from the Environmental Protection Agency this month has many in the renewable fuel industry hoping that federal agencies will get on the same page.

That’s because for the last few years, the EPA and the Department of Energy have been at odds, with taxpayer money creating a new biofuel industry that may not have the room to grow outside the lab.

"You know the right hand isn’t always understanding what the left hand is doing,” said Geoff Cooper, vice president of the Renewable Fuels Association.

The Department of Energy spent hundreds of millions on biofuel research in the last two years, announcing another $40 million of funding in June for fledgling fuels that need a market in which to grow. But Pruitt’s EPA hindered ethanol and biofuel use in the U.S. by letting dozens of oil refineries out of federal requirements to blend it into their gasoline.

Cooper and his association lobby for ethanol and biofuels, and are harsh critics of Pruitt to the point that president and CEO Bob Dinneen said that Pruitt was “waging war” against the Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS).

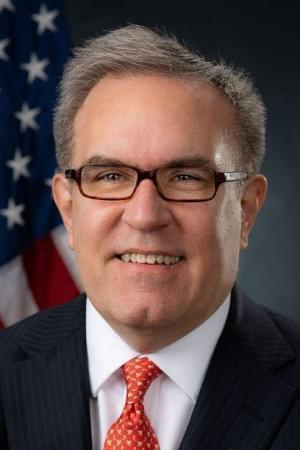

EPA acting administrator Andrew Wheeler

However, they’re hopeful the new guy, acting administrator Andrew Wheeler, will give them a fair shake. Wheeler is known for lobbying for fossil fuel companies, but he has also spent a lot of time on Capitol Hill. In his confirmation hearing to become EPA’s No. 2, Wheeler said the RFS was “the law of the land. I fully support the program.”

Iowa Republican Senator Chuck Grassley, whose state is a national leader in corn-growing and biofuel production, also expressed relief that Wheeler took over, saying July 5, the day Pruitt resigned, that he hoped Wheeler will “restore this administration’s standing with farmers and the biofuels industry.” On July 16, Iowa’s congressional delegation even asked Wheeler to uphold the RFS and stop granting waivers.

Why biofuels?

Why should the federal government be helping this industry at all? The EPA and Department of Energy did not return repeated requests for comment, but University of Illinois professor Stephen Long has an answer for that.

“You know, certainly people of my age have seen these past (oil) disruptions. You know we’ve probably three major ones since the ’70s really in our oil supplies. You know they are vulnerable, that and we know that they won’t last forever,” Long said.

Long directs a program called ROGUE. The idea is to turn sugar cane and a tall grass called miscanthus into oil-producing machines — possibly producing 20 times more oil per acre than soybeans. The sugar cane, or “energycane” as it would be known, would grow in the Southeast, while miscanthus thrives in the East and Midwest.

Miscanthus is generally grown as a yard ornament, but Illinois researcher and professor Stephen Long found that the grass was better at photosynthesis and grows more densely than many other types of plants that can survive in the U.K. and the Midwest.

The Energy Department gave ROGUE $10.6 million to be used by participating schools: Brookhaven National Lab in New York, University of Florida, Mississippi State University and University of Illinois. That’s on top of the $115 million the University of Illinois received from the DOE last year to become the nation’s fourth Biomass Research Center.

ROGUE’s plan includes growing energy crops in “marginal” fields where landowners can’t make much money from food crops. That preserves other land for feeding a population that’s expected to keep growing, Long said.

The research will use tools like gene guns and CRISPR to edit genes, things that Europe frowns upon, he said. But between new technology and the abundance of land in the U.S., Long said America is poised to be a leader in biofuels, possibly alongside Brazil.

If all goes as planned, Long said he hopes to see oil-rich energycane and miscanthus ready for mass production in the next 20 years. It takes a long time, which Long said is why it’s important to start doing now.

Tim Mies is the director of operations at the Energy Farm. He stands next to a small plot of miscanthus, and says this sections of the perennial grass will grow 12-15 feet tall.

“So it would make sure that our children and grandchildren do not go through what we saw with being held hostage over oil supplies from other countries,” he said.

Climate change

Biofuels could also mitigate climate change, with plants taking carbon from the air and stashing it in soil.

Reducing emissions was even one of the main reasons Congress created the Renewable Fuels Standard. According to the EPA, it was meant to “reduce greenhouse gas emissions and expand the nation’s renewable fuels sector while reducing reliance on imported oil.”

Oil companies often argue it has outlived its purpose, pointing to stagnant emission levels in the U.S. and an abundance of oil thanks to fracking, an advanced drilling technique.

“The RFS is a broken policy, and its continued implementation could result in dire consequences for the broader economy, as well as negative impacts on consumers,” The American Petroleum Association warned, calling for the RFS to be repealed or “significantly modified.”

Still, Long argued, his research is for the long game, when even fracking can’t meet the U.S. demand for oil. Long said battery-powered cars charged with wind and solar energy will likely be widespread, but plant-based oils can help fill the gaps in diesel trucks and jet fuel.

Stephen Long (right) stands with Don Ort at the University of Illinois Energy Farm. Long directs the ROGUE program and Ort is the co-director.

“For planes, which we’re very dependent on in the United States, we don’t really see those wind turbines and solar cells doing anything for that,” he said.

The Energy Information Administration found the globe should have fuel until at least 2050, but trade can make getting fuel to countries that need it a bit more complex.

The Department of Energy isn’t alone in trying to find solutions, though. The U.S. Department of Agriculture is also funding biofuel research, focusing on how to turn leftover biomass like crop stubble and tree branches into energy or products.

Timothy Connor with USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture said that while the agency is looking at energy security and energy diversity, his department is really focused on adding value to byproducts on farms and forests in rural areas.

“And USDA is permanently focused on that grower value,” he said.

Connor does caution that there are scientific and technical hurdles to climb first, but he has been seeing big steps forward so far, “so, we’re really excited.”

Follow Madelyn on Twitter: @madelynbeck8