Do Campus Sexual Misconduct Policies Allow Harassment To Persist?

Documents from a University of Illinois investigation detail complaints of sexual harassment against Professor Jay Kesan. Illinois Newsroom

Every college campus has standards and policies to prevent sexual harassment. But time and again, repeated complaints are filed against professors for saying and doing inappropriate things — yet they often keep their jobs. Documents and interviews from two recent cases on campuses in Illinois shed some light on the reasons why this remains a persistent issue at many schools.

Not ‘sufficiently severe or pervasive’

Students at the University of Illinois recently packed the law school library in Champaign. They demanded the town hall meeting of campus officials to get answers about why one of their law professors is still working on campus.

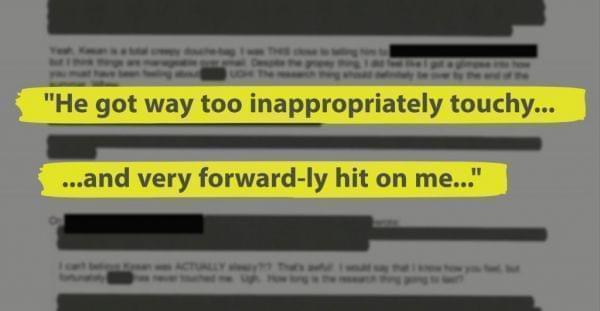

A few days earlier, a campus investigation had been made public. It showed numerous women had come forward saying U of I law professor Jay Kesan sexually harassed them.

Campus officials, including the law school dean, sat at the front of the room as, one by one, students came to the microphone to voice their concerns.

“There are a lot of students who are frustrated… and feel uncomfortable,” said one third-year law student.

Another student, who had taken a class with Kesan, said that even without knowing about the allegations, she and other classmates were uncomfortable with him.

Documents from a University of Illinois investigation detail complaints of sexual harassment against Professor Jay Kesan.

“We want an apology for not doing enough to protect us,” said Ashley Kennedy, president of the U of I Student Bar Association, which has demanded Kesan resign.

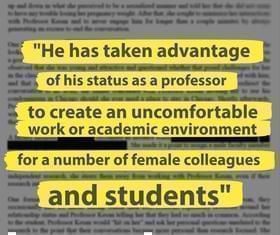

In the campus investigation that began in 2015 and concluded last year, investigators found Kesan made many female colleagues and students uncomfortable with unwarranted and unwelcome references to sex, as well as unwanted invitations and touching.

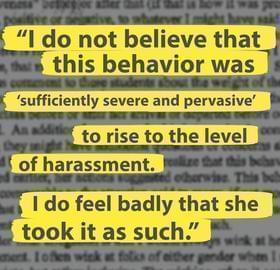

Kesan initially denied the accusations. And while investigators said he behaved in a way that “a reasonable person would know to be inappropriate for the workplace,” they deemed his actions were not “sufficiently severe or pervasive” to constitute a violation of campus policies prohibiting sexual misconduct and harassment.

While the U of I knew about this problem with Kesan for at least several years, it only went public after Kathy Lee, a friend of several of the victims, spoke out.

Lee said allowing Kesan to still teach “seems inappropriate given the number of witnesses and claimants who have had things to say about him and his sexual harassment of them.”

In a statement, U of I spokesperson Robin Kaler said the campus took “swift action” once the investigation was finalized to make sure no further violations occur.

Kesan was required to undergo in-person sexual harassment training and was excluded from certain salary programs and other honors and recognitions for a limited time.

On November 8, three weeks after the Kesan sexual harassment case was made public, the law school announced Kesan will take an unpaid leave of absence for one year, starting January 1, 2019. Kesan also waived his confidentiality rights to information surrounding the misconduct described in the campus investigative report.

Kesan also issued an apology, which reads, in part: “It was wrong of me to engage in the conduct described, correctly, by the complainants… It was wrong for me not to consider the harms that such conduct can create… I am deeply sorry.”

‘Institutions protect themselves’

Earlier this year, a former professor at Lincoln Land Community College in Springfield retired after facing a seventh formal accusation of harassment and inappropriate behavior.

Documents obtained from Lincoln Land through the Freedom of Information Act contain claims that Gary Swee sexually harassed several students. The accounts go back nearly two decades.

In 2004, five students out of a class of nine alleged misconduct, according to the documents. They said he openly called one student a “bitch” and also implied sexual invitations.

Pulled from professor Gary Swee’s response to accusations of harassment.

One former student, who doesn’t want to be identified but whose claims are referenced within the campus documents, said when she started a class with Swee, he seemed “like a cool, funny guy” at first. But things changed.

“I remember him talking about masturbation a lot, so that kind of made it uncomfortable of course. And then the stuff started to get even more personal towards me,” said the student.

She said he made repeated references to her breasts during the course she took in 2015. While it was presented in a joking manner, she said it troubled her. She said she also recalled an instance of Swee openly calling a student a “bitch” in front of the class.

She said she dropped the course because of him, and ultimately, she dropped out of school entirely.

Swee declined to be interviewed for this story, but in a brief response to request for comment, he wrote, “I have spent much time and energy defending myself to no avail. I do not want to continue to address this subject. I did not/do not sexually harrass (sic) students. I have never asked for nor received any inappropriate response as a condition for a grade.”

In previous written responses to the administration after being reprimanded, Swee admitted his teaching style might offend some, and said he urged students who were uncomfortable to come to him with their feedback.

Polly Poskin of the Illinois Coalition Against Sexual Assault said that sort of dynamic is not conducive to a healthy learning environment. “Students know about retaliation. Students know in the end who holds the power. (He was) setting students up to fail,” she said.

Poskin said higher ed frequently drops the ball when it comes to handling harassment claims. And in her mind, at the center of the problem is deeply ingrained societal sexism. “We do not take sexual harassment and sexual assault and sexual abuse seriously because it’s primarily perpetrated by men against women and it’s primarily men who control institutions,” Poskin said.

Madeline Klyczek took a course of Swee’s in 2014. She said the fact the school knew about his ongoing behavior but still allowed him to teach makes it seem as though “he was being pretty protected by the school.” Klyczek became aware of the history between Swee and sexual harassment claims through an article in the Illinois Times published around the time of his retirement, earlier this year. While some found his humor edgy and offered positive reviews, others, like her, were disturbed.

Klyczek said if the school had handled the students’ claims before her differently, it may have prevented what happened between her and Swee.

She said she went to his office to check in after missing an exam while out sick. When the topic of her interest in medieval art came up, things became inappropriate, according to her account. She said Swee told her that back in medieval times, “I’d be raped whenever anyone wanted to have me. And that if it was socially acceptable … he would do that, to me, right there in the office.”

Pulled from professor Gary Swee’s response to accusations of harassment.

Klyczek said she never officially reported what happened, and figured she’d persist through the discomfort long enough to make it through the course. She said when he handed her her final grade of a “C” he told her, “We both know you could have done better, babe,” with a wink.

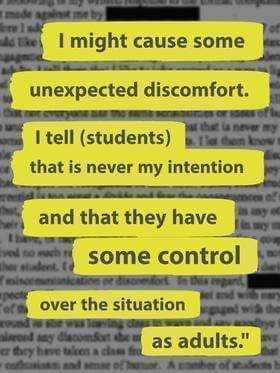

Swee’s responses to other claims are included in the documents obtained from campus. He wrote that he considered some students and former students to be friends, and that he often joked with friends in ways some might find offensive. In one instance he wrote, “I understand that not everyone has the same sensibilities or ideas of humor and that I might cause some unexpected discomfort. I tell (students) that is never my intention and that they have some control over the situation as adults.”

Poskin, with the Illinois Coalition Against Sexual Assault, said that kind of language comes off as victim-blaming.

While Swee was reprimanded by administrators at Lincoln Land multiple times, according to the documents, the school didn’t give him an ultimatum to either quit the behavior or face dismissal proceedings until another formal complaint surfaced in 2016.

Institutions are often concerned first and foremost with self-protection, according to Poskin, and firing professors over sexual harassment sets them up for ridicule and potential lawsuits.

“Institutions protect themselves. They protect themselves from liability, and they want to protect their reputation,” said Poskin. “And that’s particularly important in universities, because they are asking parents to relinquish an incredible amount of money and their children to their care.”

In response to an interview request with school officials, Lincoln Land provided a written statement. It read, in part, “LLCC does not condone any harassing behaviors. In the instances in question the college took progressive disciplinary action (verbal and written warnings, suspensions and notice to remedy) as we were able with a tenured instructor. We work within our legal and contractual constraints as students are willing to come forward and provide formal complaints.”

Reviewing campus policies

In both of these cases involving allegations of sexual harassment, administrators said they followed campus policies and took steps to prevent further violations.

But the public wasn’t informed until the news media obtained documents from the investigations.

Laura Beth Nielsen, a legal studies professor at Northwestern University in Evanston, said a complex set of federal and state laws offer an incentive for universities to keep these things secret.

Pulled from an anonymous complainant against professor Gary Swee.

“And of course, the university doesn’t want the bad publicity, and they don’t want the lawsuit from whoever might be terminated,” Nielsen said in an interview on the public radio talk show The 21st.

U of I officials have said they’re reviewing campus policies and processes to consider any changes that may be needed.

Nielsen said one simple policy change universities can make to protect students is ensure that, at a minimum, the public is informed when an investigation turns up a violation or when a settlement is made with a victim.

“In a way, all taxpayers have an incentive to push for that kind of policy, because this is our tax dollars being used to settle sexual harassment lawsuits while people continue to be employed, Nielsen said.

But until laws and campus policies change, she said, victims will be left to take matters into their own hands, filing lawsuits and going public with their stories.

And many professors facing allegations of harassment will carry on as usual.

Editor’s Note: Updated November 9 to include Kesan’s apology statement and the announcement from the U of I College of Law that Kesan will take a one-year, unpaid leave of absence, effective January 1, 2019.

Links

- U Of I Law Professor Accused Of Sexual Harassment, Found In Violation Of Campus Code Of Conduct

- U Of I Law Professor: Power Dynamics Make Academia ‘Ripe For Abuse’

- U Of I Law School Dean Apologizes For Sexual Harassment Case Involving Professor Jay Kesan

- U Of I Law Students Demand Resignation Of Professor Accused Of Sexual Harassment

- Sexual Harassment Researcher: Most Workplace Training Falls Short

- Does Sexual Harassment Training Actually Work?; Rep. Bill Foster On Funding For National Labs