Babies Expect Leaders To Address Unfairness, New Study Finds

Renée Baillargeon is a psychology professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where she studies child development at the Infant Cognition Lab. Kwame Ross/University of Illinois

Babies in their second year of life expect those they view as leaders to intervene when they see someone not being treated fairly, according to new research from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The findings are reported today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study adds to the growing evidence that young children have a well-developed understanding of social hierarchies and power dynamics, said lead researcher Renée Baillargeon, a psychology professor at the U of I’s Infant Cognition Lab.

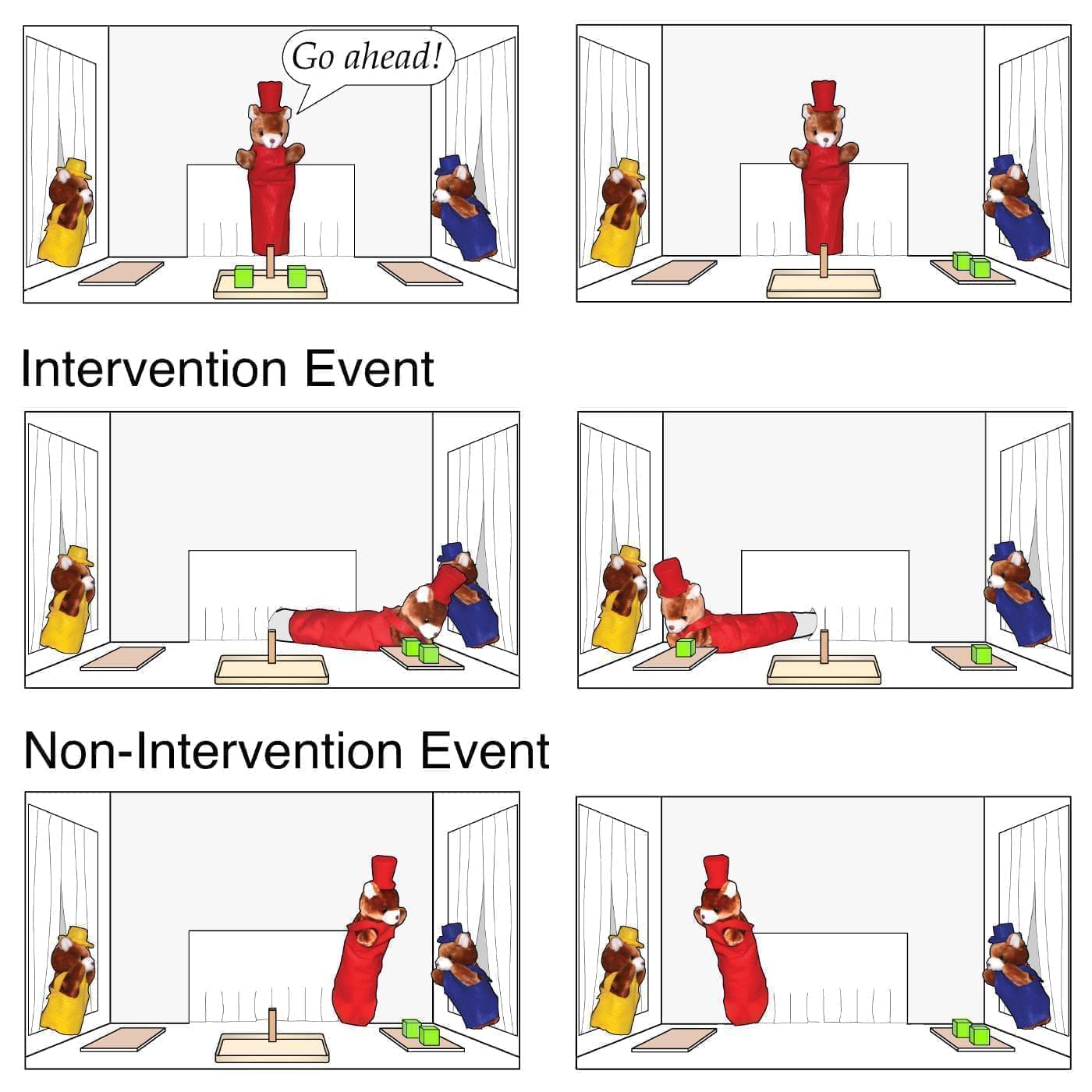

Infants in the study watched as a protagonist bear, in red, either intervened to redress a wrong perpetrated by the bear in blue against the bear in yellow, or ignored the transgression.

Researchers used bear puppets to enact skits for 17-month-old babies, who sat comfortably on a parent’s lap.

The skits portrayed different scenarios. In one, the puppet leader intervened when one of the other puppets hogged all the toys; In another, the leader did not intervene to redistribute the toys, which Baillargeon said bothered the babies.

In puppet scenarios where there was no clear leader, babies did not have this expectation of an intervention.

“What we're showing is that when these transgressions occur, babies evaluate parents and other leaders (as if to) say, ‘Well, you saw this transgression, you know this is not fair. Are you going to do something about it? And if you don't, then you are shirking your responsibilities,” Baillargeon said.

Baillargeon said the study, which involved 120 infants, supports the idea that babies are born with an understanding about power dynamics that then gets shaped by the culture they grow up in.

Alan Fiske is an anthropology professor at the University of California, Los Angeles who studies human relationships; he was not involved in this study.

You might think (babies) don’t understand the world because they don’t seem to be very competent at doing things in the world. But amazing things are happening in their minds."Alan Fiske, UCLA anthropologist

Fiske said the study builds on prior research that finds babies understand the idea of authority or leadership.

“It shows that they expect a leader to not just use power for his or her own self-interest, but to use their authority to regulate the morality of their followers,” Fiske said.

It’s common for people to underestimate what babies are capable of understanding and figuring out about the world, he said, since babies develop slowly in their physical abilities.

“You might think they don’t understand the world because, you know, (babies) don’t seem to be very competent at doing things in the world,” Fiske said. “But… amazing things are happening in their minds. They understand an enormous amount.”

Baillargeon spoke with Illinois Public Media about the study, which was conducted by her former graduate student Maayan Stavans.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity:

CH: Many parents may not be surprised that babies get frustrated when they see something that’s unfair. Was this not well-understood from a research perspective prior to this study?

RB: The idea that a young child would be frustrated when they are treated unfairly, or when they see someone else being treated unfairly, that was indeed well established prior to our study. What we’re asking here is about the response of the leader, such as the parent or the daycare teacher.

Babies evaluate others constantly, with reference to: Are you acting fairly? Are you acting in accordance with your responsibilities as a leader?

So what we're showing is that when these transgressions occur, babies evaluate parents and other leaders and say, ‘Well, you saw this transgression, you know this is not fair, are you going to do something about it?’ And if you don't, then you are shirking your responsibilities, and it makes you less of a leader, less of a parent.

Babies are born with these abstract expectations, which prepare them for their social environment. Nature, evolution gives them a whole host of principles, concepts, and expectations that help them represent events the right way, so that they can quickly reason and learn about them.

CH: How did you actually go about studying this? Because a one-and-a-half year old can't say, "Hey, that's unfair." How do you actually measure when a baby feels that something they are viewing is not fair?

RB: We relied on a well-established method that's used by many researchers in the field, it's called the “violation-of-expectation” method. It's a looking-time method.

Like most methods that are used with babies, it takes advantage of babies' natural responses. In day to day life, when babies are looking at the world and events are unfolding, they're trying to predict how the events will progress. When something doesn't go as expected, they tend to look longer at it, because it means their model of the world wasn't quite right, they expected A but they see B. So something is wrong, they have to revise their model of the world so that next time they can better predict events.

In this case, what we showed infants is a leader of a group who intervenes when seeing a transgression within the group, and a leader who doesn't intervene. And babies look longer when the leader doesn't intervene. When the protagonist is a non-leader, they look equally at the two events. So it's not that they prefer non-interventions in general, it's only when the protagonist is a leader that we see that surprised response.

In another study in the same paper, Maayan found that if the victim says she doesn't actually want a toy, then babies no longer think that the leader should intervene. So if there is a transgression, if these two puppets wanted to have a toy and one took both, leaving none for the other, babies do expect the leader to intervene.

Babies evaluate others constantly, with reference to: Are you acting fairly? Are you acting in accordance with your responsibilities as a leader?Renee Baillargeon, UIUC psychologist

But if one of the puppets says, ‘No, thank you, I don't want any,’ then babies think it's unexpected enough for the leader to intervene. Why would she redistribute the toy since the puppet said she didn’t want one? She made that very clear, making it acceptable for the other puppet to take both toys. So these are very context-sensitive expectations. When there really is a transgression, the leader has to step up and correct the situation. But when there isn't a transgression, the leader shouldn't step up; it's kind of overbearing to do so.

CH: Are there lessons here, for parents or for caregivers or people who work with small children? What are the takeaways from this research?

What this is telling us is that babies have a very abstract expectation of authority figures, they think leaders have responsibilities or obligations to take care of their followers. If a member of a group is wronged, they expect the leader to step up and do something about it.

And what that means is that if you don't, then you are less of a leader or less of a parent. Babies evaluate others constantly, with reference to: Are you acting fairly? Are you showing proper in-group support? Are you acting in accordance with your responsibilities as a leader? And you are either a good one or not so good one. When you see a transgression as a leader and you simply ignore it, then you are a little bit less of a leader in their eyes.

CH: It’s fascinating to just think about how the minds of babies work and how they really operate very similarly to adults, even at such a young age.

Babies are born with these initial expectations or principles, but each culture makes decisions about exactly how to implement them, and about which ones to give more emphasis to. Also, when two moral principles suggest different courses of action, cultures make decisions about which principle should be given priority. Do you go with ingroup support or do you go with fairness, for example.

In some cultures, you have to go within group support over fairness, so there's rampant nepotism. In other cultures, you go to jail if you do that; fairness is considered more important.

We are fascinated by this universal picture of moral cognition that babies are born with, that orients them to think in the right way about their social world. And then they learn from their cultures exactly what to pay attention to, how to implement it, and so on. It's very fun research!

Follow Christine on Twitter: @CTHerman

Links

- Under New Illinois Law, Parents Of Justice-Involved Children Don’t Have To Trade Custody For Treatment

- Summer Food Programs In Illinois Provide Meals To Children When School’s Out

- Report Highlights Racial Inequities Among Children

- Legislation Session Preview; Fake News; Children Coping With Disasters

- Champaign-Urbana Schools Seeking Mentors To Support Immigrant Children

- State Agency Proposes Changes To Reduce Children’s Exposure To Lead