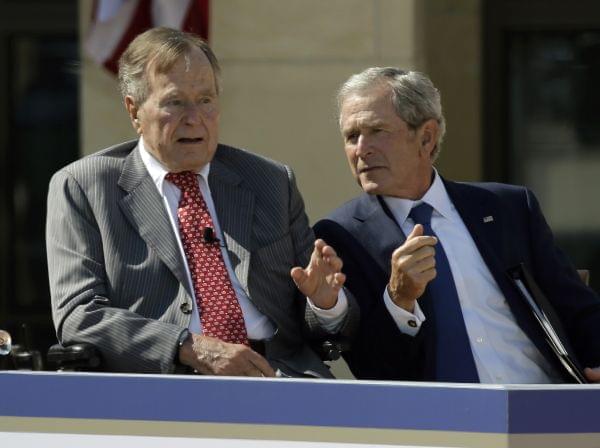

5 Presidents Appear at Bush Library Dedication

Will history judge George W. Bush more kindly than his contemporaries have?

The man himself seems fairly indifferent.

"I don't think he really cares much at all, to be honest with you," says Kevin Sullivan, who served as White House communications director during Bush's second term. "I think he cares very little about where his approval rating stands today, compared to 2005 or 2008."

His supporters care. With the opening of his presidential library and museum Thursday in Dallas, they have been making the case that he will be like a latter-day Harry S. Truman — derided as he left office, but seen as a success later on.

"The perspective of history will treat Bush better than Bush is being treated now," says former GOP Rep. Dennis Hastert of Illinois, who served as House speaker for much of Bush's tenure.

Many historians are skeptical, saying they doubt that Bush's accomplishments will be held in higher regard in years to come than they do now.

Given the 43rd president's record on transparency, meanwhile, they say the opening of Bush's library won't do the single most important thing that might revive his reputation — give them any kind of early look at the still-classified documents it holds.

"The only way history is going to change its judgment of him is if the information is available," says Emily Sheketoff, who directs the Washington office of the American Library Association. "If he wants to rehabilitate his reputation, he's going to need to be a lot more open and expansive on why he did certain things."

Long Road To Judgment

Bush's new $250 million library, on the campus of Southern Methodist University, will be the staging ground for efforts at burnishing his legacy, including a policy center that will explore and promote his ideas.

"The Bush library is the first stage in what will be a multistage operation," says Jeremi Suri, a University of Texas historian.

Former President Bill Clinton joked at Thursday's dedication ceremony that the Bush library "was the latest, grandest example of the eternal struggle of former presidents to rewrite history."

Unlike some other former presidents, Bush himself hasn't tried much to "work the refs" — appealing to historians and the public by making a case for himself through multiple books (like Richard Nixon) or good works (like Clinton and Jimmy Carter).

When asked in 2004 by the journalist Bob Woodward how history would judge the war in Iraq, Bush said, "History. I don't know. We'll all be dead."

That's not because Bush has no respect for history, says Sullivan, his former communications aide. He had a sense of himself as part of the "sweep of history" in holding his office, and he loved telling visitors about which presidents had used his desk, the Resolute, which was fashioned from the timbers of a wrecked ship in 1880.

"He would look at the George Washington portrait in the office," Sullivan recalls. "He'd say, 'They're still writing books about the first GW, and I'll be long gone before history gives its final take on his time.' "

A Fuller Portrait

In other words, Bush is content to allow history to make its own judgments. But that can only happen, historians say, when they can get a look at his administration's documents.

"If I were sitting there advising the president — which ain't going to happen — I'd say your best bet is to get as much available as soon as possible in every conceivable way," says Lewis Gould, author of a history of the Republican Party. "Bush would be best served by opening as much as he can, as soon as he can."

Historians tend to grow more sympathetic if they can see the reasoning behind a policy, Gould says. He notes that Lyndon Johnson became an object of fascination for historians as his papers became available. Even Warren G. Harding enjoyed a brief "bump upward" in the 1960s when his archives were opened.

"The way you get ahead in the history business is being able to say, 'I'm the first to find X and I have new material,' " Gould says. "That's what revision is about. It's not about bringing somebody up or tearing somebody down."

Most historians seek to be fair in their judgments of the past, but some liberal historians have been criticized for rushing to judgment on Bush, whom they largely deemed a failure even before he left office.

The Onion recently ran an article headlined, "History Licking Its Chops to Judge George W. Bush."

But new information can change minds. Princeton University historian Sean Wilentz, who wrote a widely-noted article in 2006 asking whether Bush was the worst president in U.S. history, says he might shade it a little differently now. He was more impressed with Bush's later performance, including the bank bailout known as TARP.

"I don't think this administration is going to be judged terribly well, but it's true that the last two years were different," Wilentz says.

Documents Make The Case

If new information can affect judgment, what historians and other researchers need to see at this point is the paper trail the Bush presidency left behind. Despite all the fanfare of the library's opening, they don't expect to get their hands on the documents anytime soon.

Under the terms of a post-Watergate law, most records are supposed to be open to the public a dozen years after a president leaves office. The reality is, things rarely move that swiftly.

Nate Jones, who coordinates Freedom of Information Act requests at George Washington University's National Security Archive, notes that his group has been trying since 2004 to get access to a document in President George H.W. Bush's library regarding a confrontation that occurred back in 1983.

"For historians who want to come through the files, there's not going to be anything available for quite some time," Jones says. "Very little is available at the Clinton library, or even at Reagan's."

If Bush wanted, he could push to have many of his records released early, as Lyndon Johnson did. But there's nothing in his performance as president that suggests he favors such openness.

John Ashcroft, Bush's first attorney general, encouraged federal agencies to resist Freedom of Information Act requests. Vice President Dick Cheney created one of the administration's earliest controversies by refusing to release information about his meetings with energy company executives — a fight that went all the way to the Supreme Court.

During his first year in office, Bush signed an executive order allowing former presidents and their heirs to keep records sealed for an indefinite period of time, for any reason. President Obama revoked that order on his first full day in office.

If Bush wants history to revise its early judgment, he'd better be willing to release documents, Gould suggests, "and let it hang out there with the bark off, as John Nance Garner said."

"He's got about a five- to 10-year window to hope for a reappraisal," Gould says. "If you don't let anything out, the negative interpretation will become fixed, and then there's no amount of documentary release that's going to make any difference."