Our Journey: Stories of School Desegregation and Community in Champaign-Urbana

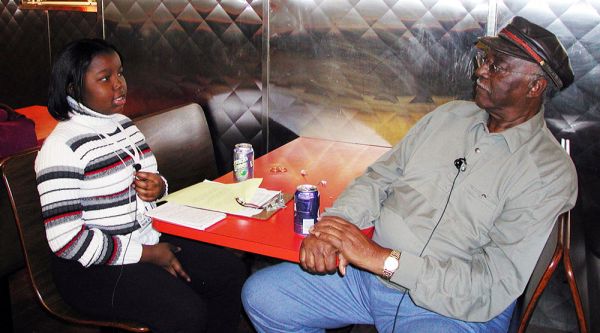

Tiera interviews Arnold Yarber in his restaurant, Po' Boys, in 2003.

Kimberlie Kranich

Our Journey: Stories of Desegregation and Community in Champaign-Urbana.

Produced in 2004.

Tiera Campbell

Hi I'm Tiera Campbell from Franklin Magnet Middle School. Welcome to "Our Journey: Stories of Desegregation and Community in Champaign Urbana." Fifty years ago, Brown versus the Board of Education made segregation in public schools illegal. While there was no law in Illinois prohibiting African Americans and Caucasians from going to school together, there was segregation across Illinois and Champaign-Urbana. We faced de facto discrimination in jobs, housing, and in public schools. Six other students and I interviewed a dozen local African American adults from age 40 to 91 to learn about their childhoods, educational experiences, expectations and their role models. This radio program will provide a window into what it was like for African Americans to live outside of the educational system while living within it. Although African Americans and whites coexisted in Champaign Urbana, and attended integrated junior and senior high schools, we endured segregation in daily living, we were discriminated against when we went to buy a house, eat in a restaurant, swim in a public swimming pool, go to a movie and look for a job. Our journey begins in 1937. That's when Mrs. ERma Scott Bridgewater, who's 91, graduated from the University of Illinois with a degree in sociology.

Tamika Lee

What was your first job when you graduated college?

Erma Bridgewater

My first job was as a maid at Newman Hall.

Tamika Lee

What?

Erma Bridgewater

Well, I looked for a job and couldn't find any in that my mother was working there at Newman Hall. And I felt like I had to help repay my parents for the money they'd spent for me to go to school. So I got a job there. And we're, I think, this couple of years. I didn't want to leave town. I didn't want to leave Champaign. I don't know if it was because I was scared of what but I never wanted to leave. I always want to stay here.

Tamika Lee

What was some experience being a maid at Newman Hall?

Erma Bridgewater

The thing I guess that bothered me most was there was a woman there that was head of it. I think it was $1.60 an hour, we were making them. And every time I got my pay, some of the money was gone. It seemed that she would take some money out of it. Because she figured that she was teaching us. That part always bothered me. And she let my mother go. And I don't know why she thought I'd stay there after she did that. But I quit.

Hester Suggs

My sister finished up here are the university, but she couldn't be hired in Champaign, they hired her down in Morris Brown College because of the university had an arrangement that was they would send them down to Morris Brown College. But even earlier than that, I had an uncle who finished in engineering, but he had to teach math down in the St. Louis area, but you had to go to an all Black school or an all Black college to teach at that particular time.

Veronica Martin

What do you do for a living now?

Arnold Yarber

Well, I have this little barbecue pit that I've had for a number of years.

Veronica Martin

Is this really what you wanted to do?

Arnold Yarber

No, no, this is not what I really wanted to do. I wanted to be a chiropractor. And I went to school and I finished chiropractic, and I never did get my license because we're coming up at that era. Going to school, the chiropractic schools did not accept American Negroes.

Catherine Hogue

I had applied at the phone company here in Champaign, right out of high school, knew I knew everything and could do this job, could not get hired in Champaign, subsequently moved to Chicago, got hired in Chicago. Five years later, I'm back in Champaign as probably the second Black supervisor at the telephone company.

Hattie Paulk

I had more education than this guy had more experience working with children and yet and still he was hired for the job because he was White and I was Black. To give me a remedy, they hired me, but as his assistant, and he pulled out a gun and held it up when I asked him for a tape measure, and that was to frighten me. And he said to me, "I'm gonna get you. " After pulling out this gun. I said, "When you get me, you better make sure you get me good." So one of the things that I made up in my mind a long time ago, I will not, under no circumstances, allow someone to discriminate against me, when I know that it's not right.

Tiera Campbell

Without a good job, it's hard to find good housing. African Americans were steered into some neighborhoods and away from others.

Hester Suggs

The first house that we bought, they would tell you in a minute that there was a gentleman's agreement that they wouldn't sell you a house anyplace else, but in certain areas. And they would, at that particular time, they were bold enough to come out and tell you that that's the way that it was, you know, and so you had to either go into certain neighborhoods, or you had to find somebody, a private homeowner who would sell you a house individually without having to go through real estate agents. And I mean, that's the way that things were at that time.

Kathleen Slates

Everybody around me lived in substandard housing. So, you took for granted that your house was okay. I mean, I lived in a house that was set right on the ground. We had rats, I don't mean mice. I mean, rats. I grew up in a house with my aunt's children. And they were bitten by rats. These were things, substandard housing in northeast Champaign was a given. Thank God, we had a fire in that rat infested place, and it burned down. None of us were hurt. But it allowed us to move to a different house. When we moved into Birch Village, that was the first time we ever had indoor plumbing and running water. That was the first experience for us. There was segregation. I just did not realize it at the time.

John Lee Johnson

I had White friends at the time I was at Champaign High School. But none of these kids lived in my neighborhood. We only saw each other at school. And I had white friends that were friends, friends, friends in a lot of different things. I didn't go to their home; they didn't go to my home. We were sitting at the same lunch table, we may talk to one another in class, we may walk down the hall speaking to one another. But we didn't visit one another our communities were separate.

Arnold Yarber

There used to be the dime store right down here on Neil Street. You go there and you can eat. It had an L-shaped counter, kind of like this. Like on that end was where the colored kids had to eat. And when you go down to the dime store there was no seats. But down in this end where all the seats were, were for the white kids in town. And yet we went to school together. So that's how that works. You didn't like it, but you lived with it.

Kathleen Slates

We went to the movies. We sat in a certain area. But I thought that's because that's where all my friends were. And that's where we wanted to sit. I had no idea that we couldn't sit anyplace else. So, it was subtleties like that, that were in this community that your parents didn't really talk about.

Hester Suggs

Champaign has had the same kind of history that all places had such as the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross on our lawn three times. Two times that I can remember. One time when I was a little child and my dad who had fought in World War One said "You can do that out there as much as you want to on the street. But when you come across the lawn, I've got my sharpshooters medal and you know, somebody's got had to go because I'm protecting my family." And so I guess maybe I was sort of raised up with that kind of pride. And so I always felt like, you know, my family always said you can do whatever you want to do, and they would be there to back us.

Tiera Campbell

According to Kathleen Slates, who grew up in the 1950s, African Americans at that time, knew their place, and didn't rock the boat. But that was about to change.

Kathleen Slates

Then the Martin Luther King movement started in the south, and we kind of jumped on the bandwagon at that point.

Hattie Paulk

Back during that time, I would say probably around '57- '58, or maybe later, Champaign Urbana was not integrated. It was still segregated. And one of the things that had happened is that during my teen years, African Americans were not allowed to sit at the lunch counters here in Champaign-Urbana. So I was part of that movement where we picketed W. T. Grants, but also JC Penney's, and picketing JC Penney's was because they would not hire African American employees. And one of the things that happened during that time, where we had the sit ins, we had the marches, and I was spit on and called the N word, which was not necessarily nice. And I was one of the first persons to be hired at Eisners, where I was to integrate that position. So that was a lot when you're talking about integration. And you being one of the trailblazers that you've got to take things and sometimes hold things in, that you wouldn't necessarily like to people to act that way towards you.

Kathleen Slates

The JC Penney store locally was located in downtown Champaign. Although there were a lot of other department stores down there, most of them had at least one African American working there. Now don't get me wrong, it was not a glamorous position by any means. They were operating elevators, and running vacuum cleaners and that kind of thing. But at least they had some on the payroll. JC Penney had none. So the very first church organized political movement that I remember was a boycott of JC Penney in downtown Champaign.

Nathaniel Banks

So, Bethel Church was the place that they met, and did all of their strategizing under the leadership of some very, very active ministers, not only from our church, but also from a church called Salem, and Mount Olive. The ministers of all three of those congregations were very strong advocates. So our church was right in the midst of all of that, and also our church worked with young people on campus. As a matter of fact, my great great uncle worked out here and developed relationships with the Black students on this campus, and actually had them coming to Bethel Church, They had an orchestra. He got them connected with resources in the community so that they could make a living because they have most of them had to work while they were going to school.

Hester Suggs

And so, they had a room with all of the resource materials for the Black students and the Black students would congregate there. They had all of the Black books and Black history and that's where the students came to study. And they'd feed them on Sunday evening and that was their social outlet.

Nathaniel Banks

And a lot of those people are now judges. Well, no, they're retired now, but a lot of those people were very influential people in the city of Chicago once they left here. They all spoke fondly of my uncle. So all that happened through Bethel Church.

Tiera Campbell

African American parents were encouraging their children to be all that they could be. However, African American children often received different messages in integrated schools.

Erma Bridgewater

We were given our schedules to take them home. And the parents would help us with our schedules. They would tell us not to take college preparatory courses. They didn't say it that way. But they would say that we couldn't, they didn't feel like we could pass algebra, or geometry. And my parents had decided I was going to college. So they always signed up for me to take those courses. And I took French too, and I passed it, no great shakes, but I did. But they didn't encourage us to take college preparatory courses.

Kathleen Slates

There were some counseling issues. They were pushing us to take home economics and the sewing classes, the cooking classes, the child development classes.

Catherine Hogue

It was suggested at the time that we take classes like typing, and home economics, those are the kind of and maybe that was some racism that was subtle, because I'm whistling aware that they are telling me or subtly saying to me, "Catherine, you probably going to be a housekeeper or a secretary. You know, so you need to prepare yourself for these kinds of things. Take home economics, sewing, take secretarial classes.

Ivon Ridgeway

What they thought was best for us was shop. And the same thing for the sisters was the best for them was home making. So, we disagreed with all of those. And we challenged them and my example with that as my sophomore year in my first class of my first hour everyday was German. Never did very well in it. But my point was, "How dare you tell me what I cannot take."

Martell Miller

They actually let you pick your courses, which they know you didn't know what you were really doing. But you're setting yourself up for a lifetime of failure if you didn't take the required courses and took the advanced courses and stuff like they weren't really preparing you for college or for any higher learning.

Kathleen Slates

That was just kind of the way things were but I don't believe that I ever felt like an individual teacher, whatever reason, discriminated against me because I was African American. That experience I don't think I had. I think it was it was more the entire the collective decisions that were made at that time just kind of overlooked the fact that we were there.

Tiera Campbell

You're listening to "Our Journey: Stories of Desegregation and Community in Champaign-Urbana," featuring African American residents, ages 40 to 91. I'm Tiera Campbell. Across the generations, our interview subjects shared stories of the difficulties they faced, as racial minorities in integrated schools. Mrs. Bridgewater lived in South Champaign in the 1920s. She and her brother were the only two Black children at Lincoln School.

Erma Bridgewater

During games, nobody would want to, they wouldn't want to hold my hand. But the teachers understood the problem. And they would find some other way to solve it. Some games I played, some I didn't. Some I watched. Being a child, you just play with whoever will play with you and you go on from there.

Hester Suggs

Oh, we got pulled out because they said we were making a spectacle of ourselves at that sock hop. And of course, what we were doing we were dancing with it called the jitterbug back at that particular time and all the students came in gathered. And I guess they said we were making a spectacle of ourselves because everybody was gathered around and so they called us to the office. We got put out of school. My dad brought us back and said "Nope, can't do that." And so he was always one that sort of stood behind his kids.

Arnold Yarber

Didn't too many go out for football in high school. So, I decided I was going to go out for football in my senior year at Champaign High School. So, I went to Les Moyer and I said "Les, I'm coming out for football this fall." He looked at me said (a lot of times you get a lot of hurts in your life). He said "You know what? You're going to have to be twice as good as the White boy to play now. " I looked at him. I said, "I'll play." So, when school started, I was started on the first team. I did the kicking; I did the running. There was one other kid on there. We went down, the other Negro kid, and we went on a trip to West Frankfort. I had never heard of it. And let me tell you, dear, when I got off of that bus, they looked at me so I will try to get back on that bus. What they were calling me. I couldn't get back on the bus, the other kids were coming off. So we had quite a time that night. And that was just one incident.

Erma Bridgewater

We had music appreciation, where we learned who composers of the music was, and so on the whole string of things about a piece, and then the teacher would play just a part of one and we were to write down what it was and so on. We had a contest there at Lincoln School. And I had a perfect paper and went on to the next stage from where all these different schools were together. And anybody who passed that was to go on to the state. But the only mistake they found on my paper was it said I had an extra hump on an "m." Maybe I did, I don't know. But anyhow, I wasn't allowed to go. And, of course, I always felt like there was another reason why I didn't get to go.

Arnold Yarber

I was a good student in school until eighth grade, and I had math. In my math class. It changed me. I went on to Mrs. McGinny, Miss McGinny. And we had long division and we had fractions. I went into the room. She said, "Alright, have a seat." I said, "Ok." She's like "What do you want?" I told her I want to ask her something about these fractions. She said, "OK." Three little White girls came in. I'm sitting there, she's going to help. And they start talking to her. She put her arms around them and start talking and walked away from me. I sat there and waited for her. She never did come back to me. And everything I had built up for love of people just sort of sort of vanished from me. It really did. Because from that moment on I never was good in math. Everything else. I was good at school, not math. I just could not get over what she did to me and that math class. I always held math that was the culprit. But it really and truly wasn't but this is the way she did. Miss McGinny. Never will forget her.

Hattie Paulk

I would love to be a cheerleader. We as African Americans were not afforded that. Now the boys could play basketball and those kinds of things. But as far as the girls being able to do that, that was not the case. I never saw a Black president at Franklin (Middle School)

Catherine Hogue

In the school system, my first exposure was seventh grade. It was like overwhelming. You know, it was something that you had never seen. You hadn't interacted with them. You hadn't been in gym class, you didn't take showers with them. So that was pretty much the first exposure.

Kathleen Slates

As a ninth grader, I participated in what was considered to be an elite vocal group called Vocalette. It was four freshmen. There had never been Black students in Vocalettes until our class got there. And the Vocalette instructor chose myself and two other Black students to join that group because of, I guess, hearing us in other choirs, and they took a trip. I got sick and couldn't go. But the other two girls did go. They had some terrible experiences. They were not allowed to enter the hotel through the front door. They were not allowed to eat in the same restaurant with the rest of the people. They had to take their food through the back. So yeah, there were some very definite, not so positive experiences with that.

Fannie Taylor

My brother, you know, came out at 16 cuz he couldn't take it anymore. And the way that they treated him as a Black male, and the way that Edison Middle School dropped him in the lower level of the school, in the basement in the corner with all the other Black males. It was a thing so that he could not take day after day the degrading. He could not take it. So when he wants to learn something, he'd come home. And he'd want me to help him. Because my education was on the first floor, or upstairs and his was on the lower level, with one teacher, who was supposed to had all of these bad boys that couldn't learn. Which was absolutely not true in the case of my brother, because much of what he was able to receive in education was after he got home, and we sat down and then go over his homework. Then I became his teacher. He got a job as 16. He worked as a cook - did it or years - he worked construction work. But whatever he did was honest work. But he needed to have the peace of mind in order to be able to function. And he couldn't get that in public schools.

Amaris Bailey

Were there any teachers that you felt really discouraged you when you were growing up in the middle school? Edison?

Martell Miller

Yeah, I had one teacher, I'd rather not mention his name. But we'd have Black History Month. And they would always from grade school all the way through junior high school, we talked about the same people, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, George Washington Carver, and a few others, but they never had brought into real Black history. And my sister was a Black History major. And I brought some books in the school because he told us to bring stuff from home. And when I brought it to his desk and showed him, he knocked them on the floor. And me and him had, like a little scuffle. And then I probably changed my way I looked at education.

Nathaniel Banks

The reason my band teacher had an impact on my life is because he took an interest in me, and he put me in places where I could either fail or succeed. Yeah, fail or succeed based on my own talents and my own merits. So I was able to rise through the ranks musically. Because he saw, he saw that in me. And he, I can remember us going to what they call a contest. Music contests. They had them at least twice a year. And you know, you'd get these little ribbons for the work that you did, depending on how well you did it.

John Lee Johnson

I wasn't quite prepared to go into middle school as I should have been prepared. And when I got into an integrated school setting, and questions that were being asked of us, I thought the Whites were more prepared to ask those questions than I was. And when I thought about that, I realized that they may have came into the classroom a little bit more prepared than I was prepared.

Markisha Motton

So you thought that White children were a little bit more prepared than you were. What class that? Did they have better teaching? Or did they have better homes? What caused them to be more prepared than you were?

John Lee Johnson

They had a better community from which they came from. They had the facilities in that community that we did not have. We did not have churches that had auxiliary rooms where kids could study. He didn't have libraries. We didn't have recreational facilities in which these kinds of activities could go on. As I said, we were 22 at a two-bedroom home. So, we clearly didn't have quote, unquote, "study space" in our house. We ate and shifts. I was I think, 19 before I ever slept in a bed.

Markisha Motton

What school experiences were life shaping or life changing for you?

John Lee Johnson

Well, none of them except probably my first year at Urbana as a junior. When I took a test and I did horribly on that test. And one of the retiring White teachers asked me to stay after class, which I did. And she went over the test, and it showed me how horribly I did on the test and reminded me that I had very little time left at school and I needed to get myself together if I was going to be able to do anything as an adult.

Markisha Motton

How does that make you feel as a person or as a young child?

John Lee Johnson

Well, it made me feel that I had wasted all of my educational experience, and that I had very little time to make up. And I set about trying to make up that time as best I could.

Tiera Campbell

Mrs. Hester Nelson Suggs was a principal at Booker T Washington School for 22 years. Before that, she taught at Dr. Howard and was the first Black teacher at Leal school.

Veronica Martin

When you were a principal or teacher, did you notice a different attitude or the way the younger African Americans felt between the differences between Caucasian and Black?

Hester Suggs

I don't think so. And the reason why I don't think so because I can go back and look at the successes. I think it's, it's the expectations that we have of kids and we have teachers. There's no teaching going on if there's no learning going on. And if you don't know how to teach a kid, then somebody needs to give you some pointers on how to do so. And I don't think there's a kid who doesn't want to learn, you know, sometimes we kill that, that learning spirit of our kids, or sometimes we can't recognize the learning spirit of the kids. You know, I've had some kids that come to school. The teacher says, can't learn math, they can't learn reading. He could write me three or four pages in a minute, maybe he's a second grader, the difference between a nickel bag and a dime bag, you know, but if he can do that, and if and if he can weigh and measure, I can show her how, how this is a learning situation. And how do you take that situation and capitalize on it, and turn it around and make a kid really want to learn, you know, because they're gonna learn something, some of them are gonna learn because of us. Sometimes some of them are going to learn in spite of us. And I think this is because what makes a teacher a teacher, and if you can teach kids, you can teach you all kids. And if you can't teach all kids then you need to go back and refine your learning process, because if you can't get it as an adult, how can you expect the kid to get it as a kid?

Tiera Campbell

You're listening to "Our Journey: Stories of Desegregation and Community in Champaign-Urbana, featuring African American residents ages 40 to 91. I'm Tiera Campbell. Before the Brown v Board decision made segregation of public schools by race illegal, Black children in the southern US were bused miles from home to go to Black-only schools, instead of their neighborhood schools in Champaign-Urbana. The policy was that children attended their neighborhood school. But many neighborhoods were racially segregated. Busing was used to change that.

John Lee Johnson

When our school district and most of the school districts across America responded to Brown versus Topeka, Kansas. What our school district did was they tore down all the inner-city schools, they tore down my beloved Willard Lawhead School, they built schools outside of our neighborhood, and they forced the children that were in our neighborhood to attend those schools. So, their children would not have to come into our neighborhood to attend schools. So, all of these schools citing new constructions that have occurred over the past 40 years, all occurred in the southern part of our of our community at a time where there really was there was no housing. When I was a kid, Carrie Busey was built on agricultural land. Southside was built where there was no homes. These schools are all built in undeveloped subdivisions and laid on the homes around them as a plan to not allow my kids to be bused into the Black community to have an integrated school system. The strategy was simple. If we were to be integrated with them, we would have to come to their neighborhood to experience this integration. This occurred not only at Champaign, it occurred in Urbana. It probably has occurred in every urban school system in America.

Nathaniel Banks

At that time, it was thought to be a positive. But as I look back at it, I think we need to reexamine how, how positive that was, because really what ended up happening, the Black schools, although they didn't have a lot of resources, had teachers who knew and cared about the students that they were teaching. And once those schools were closed, the best of those teachers were sent across town. And the students who formed part of that community were dispersed throughout the rest of Champaign as well. And we really haven't recovered from that yet.

Nina Patterson

And it was just really odd to me that they were able to go to school in their community, but I had to be bussed. But I just figured as a kid, that's just the way that it was. I didn't really question it a lot. I think at times, I would ask my mom why. I had issues with being the only as I got older, the only Black girl or that I was the only Black in a class or in a particular activity. And so, as I got older, I became a lot more aware and began to ask questions. So, it was a very interesting experience and is something where yes, I learned a lot but it would have been, I think, nice to have been able to go to school in my own area and not to be bussed out necessarily.

Hester Suggs

I guess I had mixed emotions about busing. Because the kids in Washington School, you know, things that we don't really talk about. My dad was a custodian of Washington School. And we don't talk about the Presidential Scholars that can the doctors and the lawyers that came out of Washington School, when it was an all-Black school and we didn't have the busing.

Catherine Hogue

Basically, my children at that time were bused purely for desegregation, not for education. They wanted to go to Bottenfield because we need this number over here. And that's why they were bused. And I continue to say that purely for desegregation.

Ivon Ridgeway

We didn't care to ride on buses. And a lot of times the bus drivers were not very nice to us. We didn't like getting up a half an hour earlier, or an hour earlier. We felt like they were not very acceptable and responsive to us when we went to that school. We felt that arrogance of the rich kids out in southwest Champaign that were there where their moms and dads have bought them cars. We didn't necessarily care for the treatment that we were receiving, because we were being bused to Centennial, and not having a choice to go. Because we lived in the north end of Champaign. So we felt like why did we have to go to Centennial, we should have been able to go to Central. Now we were fortunate in one aspect of it because it was a new school. And we had had opportunity to go to a air conditioned school, swimming pool, all of those components were there. So that was the plus.

Martell Miller

I think it would have been a good thing if they had showed us what had more Black teachers and more Black people and with the integration for it, instead of just taking the kids and shipping them to a whole new environment. And all you would see was the Whites teachers and everybody of authority and there was nobody you could really come to. I think I had a Black PE teacher at South Side, and they had a Black cook there, and at Edison they had like janitors and cooks. And I think we had, we probably had four Black teachers, five Black teachers. And today it's still about the same.

Hester Suggs

It's up to us now because we have access to make sure that we have a level playing field. By that I mean, if my kid wants to be going to algebra or trigonometry or other kinds of things, that the availability is there, whereas before the availability wasn't there. Before say that the schools in the Black neighborhoods and things you might get books that other buildings didn't want. You know, and now everybody has to at least have the same new textbooks and the same new kinds of entree to to education. I think desegregation is good, but I don't think that's the panacea to everything. You know that because the educational opportunities are there. We should be availing ourselves to them. But we should also make sure that they’re all good teachers, I think every school should be a good school.

Tiera Campbell

Across the generations, local African Americans told us how their parents and their community supported them.

Kathleen Slates

In all Black schools, we knew the teachers. Teachers knew the parents. Parents communicated on a regular basis with teachers. If you didn't get good grades, they wanted to know why. We were nurtured a good deal.

Nathaniel Banks

I can remember my mother, this happened in elementary school. My mother is the one that taught me my times tables. She just went over and over again, doing that drill and practice with flashcards and all of that, because I was having some difficulty there so that she was engaged with us in that way.

Kathleen Slates

It just made you feel ashamed. If you didn't get good, good grades. I mean, we had a lot of pride in what happened at that time? I remember crying when I got my first D.

Tamika Lee

Did your parents have any expectations for you? High expectations?

Catherine Hogue

I don't think if they did, they never shared that with me. They just always encouraged me to do my best. To be the best that I could be.

John Lee Johnson

I am from a family of 13 brothers and sisters. We lived in a two bedroom home at one point there was 21 of us who occupied this home in the northeast area of Champaign. I came up in the 40s in fact, I was born in 1941. I came up at a time in which you did not question your parents. You did exactly what they told you to do and when they told you to do it. There was never any debate. There was no television to offset my mother. We had one telephone. We were not allowed to use the telephone. We didn't have all the outside distractions that kids have today,

Fannie Taylor

I grew up without parents. My grandmother was my provider. She had very limited education. She could not read, she could not write. I would read her mail to her, I would write a response to her mail for her. It helped me to enhance my reading skill that helped me to enhance my writing skills, you know, helping her helped me. But she could not provide the guidance that I need and what to do. Or if I got stuck on something, she couldn't do it. And I'm sure that probably bothered her more than I would ever have known.

Kathleen Slates

In my case, I lived the majority of my life, young life with my grandmother. My mother lived in a different community. My grandmother had an eighth-grade education. Her sister had a sixth-grade education. These were people who didn't have an opportunity to go to school. Their feeling was you have this opportunity. You take advantage of it. And you're there to achieve. That's what we expect you to do. And it was unacceptable. For anything less. I had my first child when I was still in high school. But it was never a question as to whether or not I would finish high school, that was just a given. That's how we grew up. You can count the people on one hand that we went to school with, that did not meet that challenge.

Nina Patterson

There were some that felt that I wasn't smart enough to be in a particular math class. Or that I should be in a particular science class or a writing class. And so my mother and I, at times, we had to challenge the system. Because they'd be like, well, she can't do the work. And my mother would say, Well, how do you not she can't do the work. And she's going to be in this class, and she is going to do the work. And she's going to pass. And so my mother would make sure that when those situations came up, and she would challenge the school, and I would get in that class, and I would work and it would be challenging at times but I did pass. But a lot of times my mother had to be the advocate on my behalf for my education. Because if not, then I just would have been another Black student just going through the system. A lot of my Black friends, especially my male Black friends, that just got passed through the system.

Fannie Taylor

Nina's right. I did have to go in and raise some issues and some concerns, some eyebrows, and, you know, some people saying certain things were happening, that I knew what's happening. My work through a social service agency to work with kids, to work with teachers, to work with administrators, school administrators, I knew what they was looking at. I knew because I knew how they was treating my clients. So I was determined that I was not going to have my children - and even the kids that I was working with - as much as possible, to not have to go through a lot of trauma every day, because they were part of something that society say you must be a part of.

Markisha Motton

What people help you to shape who you are. Did you have any certain role models?

Hattie Paulk

Yes, I did. I would say that it was my grandmother. Her name was Amy Chipman. She was I would like to say that she was a businesswoman. That she would take laundry and do laundry in her home. And she had a work ethic that she would work very hard. So I think my grandmother, and then my mother, was a role model. Because I saw how my mother would take in children, taking people who did not have what we had. And she was always willing to share. And she too was a person. I wouldn't say stingy, but she didn't let people play with our money. If you older you had to pay her her money, but she accumulated houses and was able to become an entrepreneur in her own right. Being able to do that. And then my father. I think my father, my mother and my grandmother, were really my role models.

Ivon Ridgeway

There were all types of individuals in our community. They were entrepreneurs. There were, of course, ministers. We had African American teachers. And that was males and females. Principals. I went to all Black school when I first started out. So there were so many different exposures that we had. And so you could choose your idols.

Hattie Paulk

I remember one lady named Maggie Bell Johnson, who lived down the street who used to play ball with us. Your neighbors help raise you. If you acted out, they would check you. I think that it was a community effort to raise the people in our community.

Martell Miller

And helped us with our homework may got us tutors, we had like field trips showed us different things like going to baseball games, football games, museums. Showed us a lot of things that we didn't really get to learn in school.

Arnold Yarber

Going to church, and then he just had like, on Sunday evenings had five o'clock or six o'clock, they have what they call B YPU, that is young people's Union. And the kids from all the churches would meet at Salem Baptist Church. That's when you get to see your girl, like if you had one. And so that's what we'll be down there. And all the kids would meet that's on Sunday evening, as I was it had no place no joint no places like that to go. So you'll be there. You'll be talking about music and thing, but you'll be everybody be right that Salem Baptist Church in the evening. There's so many kids at the time. And we all got on as a community. It taught us a lot of things of togetherness, that's what I saw. What I really saw at the church, a lot of togetherness with all the kids, because we were all we were at the same time. We just depended on one another.

Tiera Campbell

We began "Our Journey" with the story from Mrs. Erma Bridgewater, who, despite a college degree in 1937, could only get a job as a maid. When she became director of the Douglass Community Center in Champaign a few years later, she faced a different challenge.

Erma Bridgewater

I was coming to them not knowing anything about recreation. And I was from the other side of town, and with a degree. And I just was not accepted. Because I was from the other side of the tracks and all that had been College had a degree. The way they treated me was an advantage in the end. And I was glad because it made me realize that I had to learn how to get along with people. It was a good lesson. And as I said, I had to swallow that degree and forget that I ever had it. I swallowed my degree and got along with everybody after that.

Hattie Paulk

If we look at where we are as a people, African American children, it may be worse now, in many ways, and only say that and it's hard to generalize. When I look at some of the reports that I'm reading, where African Americans have the highest suspension rates in schools. We did not have that before. When I look at the number of African Americans who cannot read, I didn't see that before. When we look at the number of African Americans, young people I'm talking about, are disrespectful to the elders. We did not have that before. So, I think with some things we've lost. Right now, you don't have as many Black role models that you all can look up to, as we had before. We saw the Black teachers, we saw the Black doctors, you've got some that's in the area now. But if you look around, do we really have that many African American professional doctors and lawyers and those kinds of things? I think we've lost some ground, and even with businesses in Champaign and Urbana, I think that we lost.

Tiera Campbell

You're listening to "Our Journey: Stories of Desegregation and Community in Champaign-Urbana," featuring stories from African American residents ages 40 to 91. I'm Tiera Campbell. What's it like for African Americans in the public schools today? Here's what some of us think.

Veronica Martin

Back then, we didn't have as many opportunities as we do today.

Tiera Campbell

Tamika, do you feel this way about this?

Tamika Lee

I think that we're better off today. And then back then. But like Veronica said, we still can improve on a lot of things. The things that improved, it don't seem that way. Don't, like that much. Like the school. People don't act like they want to be in school like they should. You know, we still got a lot to improve on.

Jessica Austin

Tamika, do you have a role model in life? And, if so, who.

Tamika Lee

I don't really have a role model. But my goal is to go to college, because I've got, like, people around me saying that. I'm not going to make it to college, because it's in my blood. But no, only a couple of people in my family has graduated. But the more people around me telling me that I'm not going to make it, it's the more that I want to make. And that's, that's what's gonna get me up and dare to believe.

Veronica Martin

Do you believe that people down you and make fun of you because you're well educated.

Jessica Austin

Well, I get a lot of comments from seventh graders at Franklin. African American seventh graders at Franklin, because I act, quote unquote, "White." And because I'm in the honors classes and everything. And I think that some like, I really kind of just ignore it, and go on with my life, because I just need to concentrate on myself. And I don't think they need to worry about me.

Tamika Lee

Just the other day somebody told me that school was for fools. And they put me down and they and I study got people putting me down, but like I said earlier, is it's making me stronger, to be who I am. And I feel like I know how Catherine Hogue and themselves when they was put down by the counselors and said to take low course jobs because people around me keep telling me, it's not right and no, it's better to drop out. Because where you gonna get when you go to school? You can't get a good job while you're in school.

Jessica Austin

Why do you? Why do you think that kids these day, say you're acting White? Or something like that? Where do you think that came from?

Tamika Lee

I don't know where it came from. But I think that kids today see it as if you ain't Yo Yo man, or if you ain't also what they call thuggin', I know what they say "pimping" or some if you ain't doing that, or getting bad grades and hanging out in crews and trying to be popular and when Sean John are getting who are basically ghetto, if you ain't ghetto, then you selling out. And but I don't think that's right to judge the person because of how they act and tell him that they selling out ourselves. Because it's like judging the person by skin color. It's not right. We've been through this project all of us together. Do you feel that you're ready to be a role model at anytime? Or if it's somebody that needs you? Do you feel that you can be there for them, you know, tutor them and mentor them, and help them through the problems.

Tiera Campbell

Um, since I've been through this program, I believe I've gotten more educated than what I was before. And I feel that anybody who, like if they wanted to write a paper about a famous Black person, anybody come to me and I mean, I can help them with the facts, the years the dates, anything, because this project, it's expanded, and it's helped me be more educated than what I am. And I've learned more than what I've known before.

Veronica Martin

I believe that I would be able to tutor somebody or help them because I've learned that all role models are not perfect. And I know I'm not perfect, but I've learned to surround myself with different people. And I've learned to adapt and understand what they're saying. And I think that if I help somebody else, that I'd be able to help them and learn from them too.

Jessica Austin

I agree with with what both of them said. But I just want to add that if someone wanted me to help them with something like this, I would want to do it a lot, because I learned a lot. And I have a lot of knowledge about all of this stuff. And I want to share my knowledge with others.

Tamika Lee

Okay, me, personally, I think that I can be a really good mentor role model for somebody because all that I've been through and all that I'm going through, and the steps that I got to make it, and I feel that I can teach a person, you know, to be strong. And you know, the best has not come yet. But you know, you still got the good times you got a whole life ahead of you.

Tiera Campbell

Well, we got to wrap up our show about the Brown versus Board decision. And I just want to say that some of the answers that you guys gave were very good. And people need to listen and take these answers that we said into head because they're very good answers and they need to think more about their education before trying to be out there trying to be the best and press their friends and anything.

Tamika Lee

Like the saying goes, "Books before boys."

Tiera Campbell

We hope you've enjoyed "Our Journey: Stories of Desegregation and Community in Champaign- Urbana." This program was produced by Jessica Austin, Yakera Barbee,Tiera Campbell, Deanna Carr, Tamika Lee, Veronica Martin and Markeesha Motton from Franklin Magnet Middle School. We conducted the interviews and edited the stories with guidance from WILL. Stories were contributed by Nathaniel Banks, Erma Scott Bridgewater, Catherine Hogue, John Lee Johnson, Martel, Miller, Hattie Paulk, Dr. Nina Patterson, Ivone Ridgeway, Kathleen Slates, Hester Nelson Suggs, Fannie Taylor and Arnold Yarber. For more information on this project, visit our website at https://will.illinois.edu/illinoisyouthmedia. "Our Journey" was directed by Kimberlie Kranich; co-director Dr. William Paterson, visiting assistant professor U of I; technical instructor Dave Dickey; Assistant Producer Shawyn Williams; Franklin Magnet Middle School teachers Shameem Rakha and Kathleen Carol. Music by Sweet Honey in the Rock. Special thanks to Franklin Magnet Middle School Principal Sandy Powell. I’m Tiera Campbell.

Elders from Champaign, Illinois' Black community share their stories of achievement and struggle with middle school girls from Franklin Middle School.Then these same students reflect on their school experiences.

Our Journey: Stories of Desegregation and Community in Champaign Urbana was created by seven African American girls from Franklin Middle School who spent their 2003/2004 school year working with public radio station, WILL, to collect oral histories from their elders and weave them into a compelling story of social and historical significance.

Featuring Nathaniel Banks, Erma Bridgewater, Catherine Hogue, John Lee Johnson, Martel Miller, Nina Patterson, Hattie Paulk, Ivon Ridgeway, Kathleen Slates, Hester Suggs, Fannie Taylor and Arnold Yarber.